Out of the Shadows: Candyman & Chicago

Image courtesy of Manuel Cinema. View more cinematic images from Manual Cinema. Photo courtesy of Universal Pictures.

by Ronia Holmes & Clare Austen-Smith

In 1992, the American gothic supernatural horror film Candyman terrified audiences and critics alike. Inspired by Clive Barker’s 1985 short story The Forbidden, the film transported the tale from a fictional White working-class housing project in Liverpool, England to Chicago’s predominantly Black Cabrini-Green, a real housing project once located on the city’s Near North Side. Director Bernard Rose’s Americanization of the story for the big screen kept Barker’s foundational themes of classism and folk culture, adding to it the dimensions of race, disinvestment, and the haunting specter of ‘urban renewal.’ Rose’s version also established Candyman’s origin story, as well as the now-iconic mirror method of summoning him that featured prominently at so many childhood sleepovers.

Horror legend Tony Todd, whose imposing presence, charisma, and rich baritone cemented the image of Candyman, developed the character’s backstory in preparation for the role. The tragic history Todd gave Candyman was described by the actor in an interview with Fangoria:

“Granville T. Candyman [was] the scion of a rich black family in 1870s Chicago. Having gained fame for his portraits and music, Granville is commissioned to paint Helen, the ravishing daughter of a wealthy landowner. Granville demands that Helen pose in the nude as Venus, and her shock soon turns into love. This forbidden interracial affair brings the city's wrath down on Granville. Cutting his right painting hand off with a rusty blade, the lynch mob then covers his naked body with honey, cheering as he's stung to death by bees.”

“Granville T. Candyman” became “Daniel Robitaille,” and this story of forbidden love and racial violence became an integral part of the Candyman mythos, infusing the character’s rage with a quiet despair that Todd displays with spellbinding gravitas every moment he’s on-screen. Robitaille’s ashes were spread over the grounds of what would become Cabrini-Green, and his murderous spirit is called forth whenever someone says his name five times into a mirror. At the end of the film (spoiler alert), Candyman perishes—but in the fashion of all great supernatural horror villains, he didn’t stay dead.

Earlier this summer, following numerous delays due to the COVID pandemic, the eagerly awaited spiritual successor to this cult classic hit cinemas. Also titled Candyman, the film is directed by Nia DaCosta, who co-wrote the script with producers Jordan Peele and Win Rosenfeld. To date, the film’s worldwide box office has grossed $77.3 million and has been praised by critics for DaCosta’s visual artistry and its chillingly effective blend of slasher horror and resonant social commentary.

Numerous critics, scholars, activists, philosophers, historians, and cinephiles have reflected on and written about the complex layers of the Candyman franchise, and while it’s all fascinating reading, our contribution is this:

Give it a watch!

To quote another classic, life’s no fun without a good scare. But what makes Candyman one of the greats of the genre has as much to do with the stories surrounding the films as with the psychological terror and blood-and-guts within them (as an aside, both films are rated ‘R’). You could spend at least half a day engrossed in how real-world horrors subtly or overtly influenced the respective visions of Candyman that Barker, Rose, Todd, DaCosta, Peele, and Rosenfeld developed. As you settle in this Halloween weekend to marathon your favorite horror films, put Candyman (both of them) on the list, and read our short list of facts and production stories that we find interesting or illuminating. We hope your thrills and chills are enhanced a little by this information.

Turn on all the lights, don’t look in the mirror, and have a fun and safe Halloween!

1. Shadow Puppetry by Manual Cinema, UChicago Alumni

Candyman (2021) Director Nia DaCosta Breaks Down the Shadow Puppet Sequence | Scene Breakdown | Fandango

Feeling a bit creeped out by shadow puppets after watching that Candyman trailer? You're not alone. The Chicago Reader deemed the puppetry interludes "whimsical and devastatingly terrifying.” They were created by Manual Cinema, an Emmy Award-winning experimental multimedia theatre company founded by UChicago Alumni (you might be familiar with their work involving another iconic horror tale, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein). The choice to use puppets to portray the flashbacks was deliberate; not only did it allow DaCosta to avoid using footage from the 1981 film, it provided crucial visual narrative without showing Black bodies being brutalized on screen. The puppetry pays tribute to the works of Kara Walker, whose silhouette works inspired DaCosta to incorporate puppetry into the film.

The puppet interludes were well-received, with Time Magazine declaring them “so effective they could constitute a mini-movie by themselves.” We’ve included the movie’s official “puppet trailer” here but you can check out the full, uncut version of the short film on Manual Cinema’s Candyman page.

2. The Shadow of Cabrini-Green

Aerial view of the Cabrini-Green housing development, looking northeast. Chicago, 1999. Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

Both Candyman (1992) and Candyman (2021) are set in Cabrini-Green. Rose’s narrative is heavy on the blight and gloom of a housing project abandoned by the very government that built it. DaCosta’s film focuses on the other side of the coin— in her Candyman, the social critique is even more pronounced: gentrification, and how cities push development forward at the expense of communities and in ways that exacerbate inequality.

“You really have to hold as many stories as possible in your hands before you figure out how to tell your singular story in the best way,” DaCosta told the New York Times, about recomposing the tale.

Chicago began tearing down the mid- and high-rise buildings of Cabrini-Green Homes in the mid-90s, and knocked down the last tower in March 2011. In the 2021 film, upwardly-mobile couple Anthony McCoy, an artist portrayed by Emmy Award-winning Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, and his partner, art gallery director/curator Brianna “Bri” Cartwright (Teyonah Parris), move into a luxury loft in the now-gentrified Cabrini Green area. In the present day, the residents of Cabrini-Green have long-since been displaced and the dilapidated projects replaced with upscale restaurants, mixed-income high rises, and grocery stores. All that remains of the original projects are the rowhouses, a boarded-up section of which features in DaCosta’s film.

At its peak, Cabrini-Green was home to some 15,000 residents. The word most often associated with the housing project is “infamous,” due to the high rates of poverty and violence that plagued the area. Rose’s cast and crew had to negotiate with local gangs to guarantee safe working conditions while filming, and Todd was advised by a cop to watch the rooftops for snipers. Yes, Cabrini-Green was a dangerous place, but it was also a community, home to thousands of people who knew hope, had dreams, and experienced joy. Former residents have recounted the ways in which they supported and loved one another, and forged strong bonds and life-long friendships. The story of Cabrini-Green is as complex and varied as the individuals who lived there. Unlike the 1992 film, the 2021 Candyman seeks to incorporate a multifaceted picture of Black people, one in which suffering and happiness are part of a continuum and triumph is possible.

Abdul-Mateen was quoted in USA Today as saying, “With our ‘Candyman,’ we're hoping to take back the narrative and the stories of our trauma from a place of victimhood and move it to a place of agency.”

While the original Candyman focused on the experiences of White, female, middle-class graduate student Helen Lyle, DaCosta’s Candyman is told through the eyes of its Black characters, both as individuals and as members of a broader community with connections to Cabrini-Green. And this is where the role of memory, of oral traditions and storytelling that underpin the franchise’s entire mythos come into play: the projects that the Candyman originally haunted may have been demolished in the name of economic development, but Cabrini-Green is not gone. It remains in the complex history of Chicago, in the hearts of the people who called it home, and in the collective consciousness of the Black community.

Just as the Cabrini-Green projects are no more, so, too, has the terrifying legend of the Candyman faded with time. But the Candyman still lurks there, waiting to be remembered.

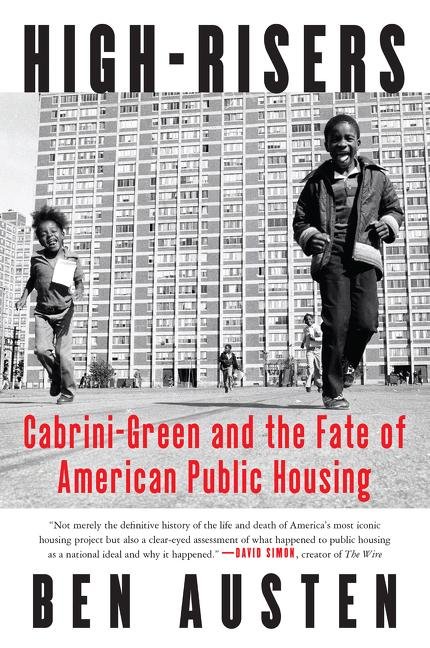

Want to learn more about Cabrini-Green? Start with the same book DaCosta did: High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing by Ben Austen, a professor in Creative Writing right here at UChicago.

3. chicago filming locations

Teyonah Parris as Brianna Cartwright in a scene from ‘Candyman,’ directed by Nia DaCosta. (Parrish Lewis / Universal Pictures)

Director Nia DaCosta and action Yahya Abdul-Mateen II. Parrish Lewis/Universal Pictures and MGM Pictures/AP

Unlike the original Candyman, which shot for six days in Chicago before moving to Hollywood, the 2021 film was shot entirely on location here in the city. In 2019, production notices were all around town, under the working title “Say My Name.” Principal photography took place mainly on North St. Louis Avenue, but some scenes were shot at Marina City (the Corn Cobs), in the South Side’s Kenwood neighborhood, and at the Old Cook County Hospital.

DaCosta’s Candyman also has the distinction of being the first feature film to shoot inside the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA).

In one scene, Bri meets with fictional MCA curator Danielle Harrington (Christina Clarke) to discuss the potential for collaboration. As the conversation progresses, it becomes obvious that Danielle’s interest in Bri is predicated on packaging and selling Bri’s tragic past and her contemporary connection to Anthony and the violence unfolding around him.

The scene is filmed against the backdrop of Virgil Abloh’s solo exhibition, “Figures of Speech,” which was on view at the MCA in 2019. In the film, Bri and Danielle stand before one of the installation’s most memorable pieces, a yellow neon sign with the words “You’re obviously in the wrong place.” Fans of the original film may read this as a callback to a line spoken to Helen in the 1992 film but it also serves to highlight another set of themes in the 2021 version: the exploitation and commoditization of Black trauma, and the uncomfortable complicity that Black professionals like Anthony, Bri, and Danielle have in the harm perpetrated against their own people. The latter point is hammered home plainly in one of the first scenes in Bri and Anthony’s sprawling loft condo, where the two are hosting a get-together to meet Bri’s brother’s boyfriend. Bri laments that the residents of Cabrini-Green were repeatedly lied to, that the CHA “…kept telling people they were gonna make it better, moving ’em from place to place, but they were just tearing it down, so they could develop everything around it.” To which the boyfriend replies, rather innocently: “Oh, like here.” The silence that follows speaks volumes and echoes in the rest of the film. Anthony and Bri are ambitious and driven but their paths to success require painful compromises against their identities and come at steep personal costs as they navigate the realities of a bourgeois art scene controlled by White people, in which Black culture is valuable but Blackness is not.

Considering the bloody demise of some characters in DaCosta’s film, it’s fair to say the art world doesn’t escape the Candyman’s wrath either.

Still, Chicago is a city renowned for its rich arts and culture, and the cinematography of DaCosta’s Candyman captures much of the beauty of the city’s art and architecture. Waters Fall From My Breast to the Sky, a permanent site-specific installation by Ernest Neto at the MCA, also makes an appearance. The MCA is accepting online reservations for visits to its galleries, so make plans to go.

4. local talent

Yahya Abdul-Mateen II in Candyman. Art in background by Sherwin Ovid. Photograph: Parrish Lewis/Universal Pictures and MGM Pictures

Step into the minds of the Art & Artists that painted the world of Candyman.

Rose’s 1992 production populated its scenes with residents of Cabrini-Green, who played extras in the film. Conflicting sources attribute this to being either a stipulation of the CHA in giving Rose permission to shoot at the projects, or part of the agreements Rose’s team negotiated with the Cabrini-Green gang leaders to guarantee the safety of the cast and crew.

DaCosta’s film also employs local talent. In addition to Manuel Cinema’s puppetry, the works of numerous local artists decorate the walls of characters’ homes. All of Anthony’s work was created by SAIC alums Cameron Spratley and Sherwin Ovid, who created the pieces that hint at the supernatural influences taking over Anthony. The production team also worked with art curator and UChicago alum Hamza Walker to create the group show depicted in the movie. Installations and artwork seen in the gallery are pieces from local artists.

Spratley, who was hired to create the protagonist’s early work, is quoted in a Chicago Tribune article: “There’s a lot of movies and TV shows with artwork in them, and a lot of the time they’re just prints — decoration…But so many Chicago artists contributed to this movie.” Check out Spratley’s work on Instagram.

In the film, Anthony has hit a wall as an artist. Desperate to keep his career from stalling, he goes in search of inspiration—and finds it in the Candyman legend. As the story progresses, Anthony’s interest spirals into obsession. The rapid intensity of Anthony’s descent into madness—and into the Candyman’s clutches—is reflected in macabre art throughout the film.

“The art within Candyman is definitely about devolution to mirror his psychological descent,” observes DaCosta in a video feature about the art and artists (watch above).

5. WHERE YOU CAN’T WATCH Candyman

Still from ‘Candyman’ (2021).Universal Pictures and MGM Pictures.

Exterior view of the New City YMCA at 1515 North Halsted Street while still under construction (demolished 2007), showing the multi-colored glazed brick facade and parking lot in the foreground. The two high-rise apartment buildings in the background are the Thomas Flannery Apartments (senior housing), now part of the Orchard Park mixed-income development on North Clybourn Avenue. Photographer: Brubaker, C. William, 1980. Courtesy of UIC Library Digital Collections.

The demolition of Cabrini-Green rippled beyond just the projects. Many local area organizations and businesses fell under the machinery of redevelopment. One of those organizations, the New City YMCA, saw a rapid drop in membership as residents were displaced. Although the New City YMCA’s membership included the wealthy of Lincoln Park and the impoverished of Cabrini-Green, it was the Cabrini-Green residents that were crucial to its sustainability. With those members gone and real estate prices rocketing, the YMCA was ultimately sold to developers and promptly demolished. In its place was constructed the NEWCITY structured development, a massive mixed-use complex of luxury high-rise apartments, retail and office space, a parking garage, and a plaza occupying a one-million-square-foot area.

From the ArcLight Chicago Facebook feed, July 2016.

The developer tasked a design studio with salvaging some of the glazed bricks from the YMCA’s famously colorful facade. These were turned into the NEWCITY Heritage Installation, a public art piece installed in the complex. The work is meant to “preserve the heritage” of the YMCA and symbolize “two worlds coming together.” Which…well, as we already mentioned, DaCosta’s film has a few things to say on that score. Of course, if any of the residents of NEWCITY want to see the movie, they’ll have to go elsewhere.

An anchor of the NEWCITY development was ArcLight Cinema, an enormous, upscale 14-screen movie theater that opened in 2015. ArcLight was, like the rest of its industry, hit hard by the closures necessitated due to COVID-19, and it shut its doors in April of this year—ten months after what would’ve been Candyman’s original premiere date. On June 18, ArcLight’s parent company, Pacific Theatres, filed for bankruptcy. As a result, no one will be able to see Candyman at the site of the YMCA-turned-movie-theater-turned-bankrupt-vacant-building next to a high-rise.

Alderman Carlos Rosa-Ramirez (35th Ward) suggests a different kind of horror may lurk around the former site of Cabrini-Green. In his article for Jacobin, he revisits the economic history of the area and considers how the thematic elements of DaCosta’s film emulate the struggles of our nation:

“‘Candyman’ isn’t just a horror film — it’s a tragedy, a documentary, real life. It’s the story of disinvestment, of forced displacement, of racist state violence. The horror of ‘Candyman’ is the horror of the United States. Don’t look away.”

Candyman (2021) is now available for viewing on demand and in cinemas.