Alternate reality game A Labyrinth offers a model for new media in a distanced age

A Labyrinth, an Alternate Reality Game, 2020 | Postmorten trailer (02:41)

Produced by Ben Kolak/Scrappers Film Group

By Ellen Wiese

How do we connect with one another when we are physically separated? How can virtual engagement simulate, recreate, and innovate in-person interaction? What kind of stories do we need now?

Interactive media has proven itself to be one of the most powerful forces in today’s world. A group of artists, designers, and technicians at the University of Chicago is pushing the boundaries of how this new media can be used to build community and shape our interactions.

From April 6th to May 13th, a team affiliated with the Weston Game Lab (WGL) and the College developed and presented A Labyrinth, an alternate reality game that utilized the setting of the UChicago campus as the playspace for a series of interactive quests. Stemming from the immediate need for community and engagement as classes and activities for Spring Quarter were moved online, this initiative asks big questions about the future of media — not to mention humanity — and begins to assemble the answers.

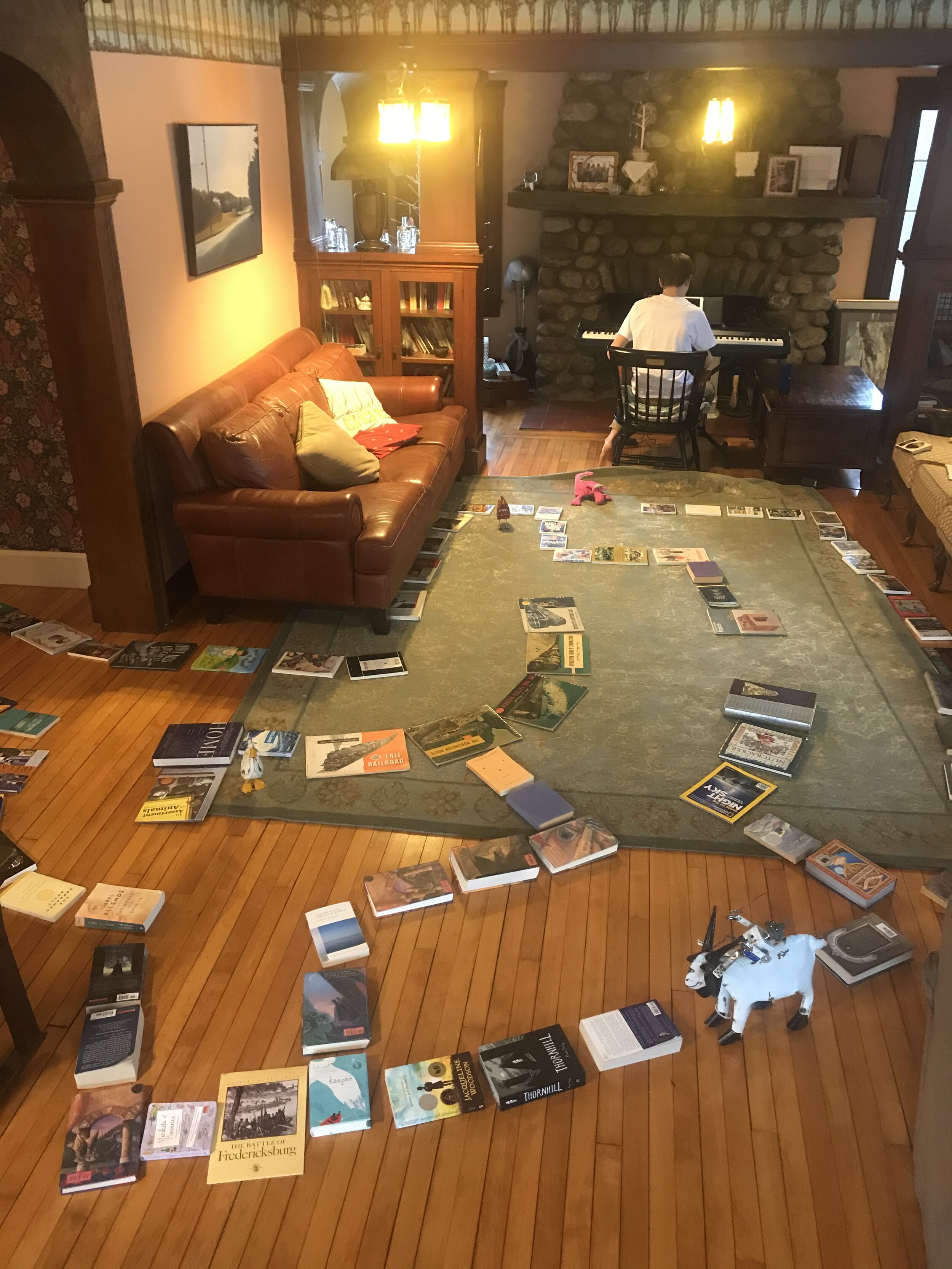

A still from A Labyrinth. Image courtesy of Ashlyn Sparrow and Patrick Jagoda.

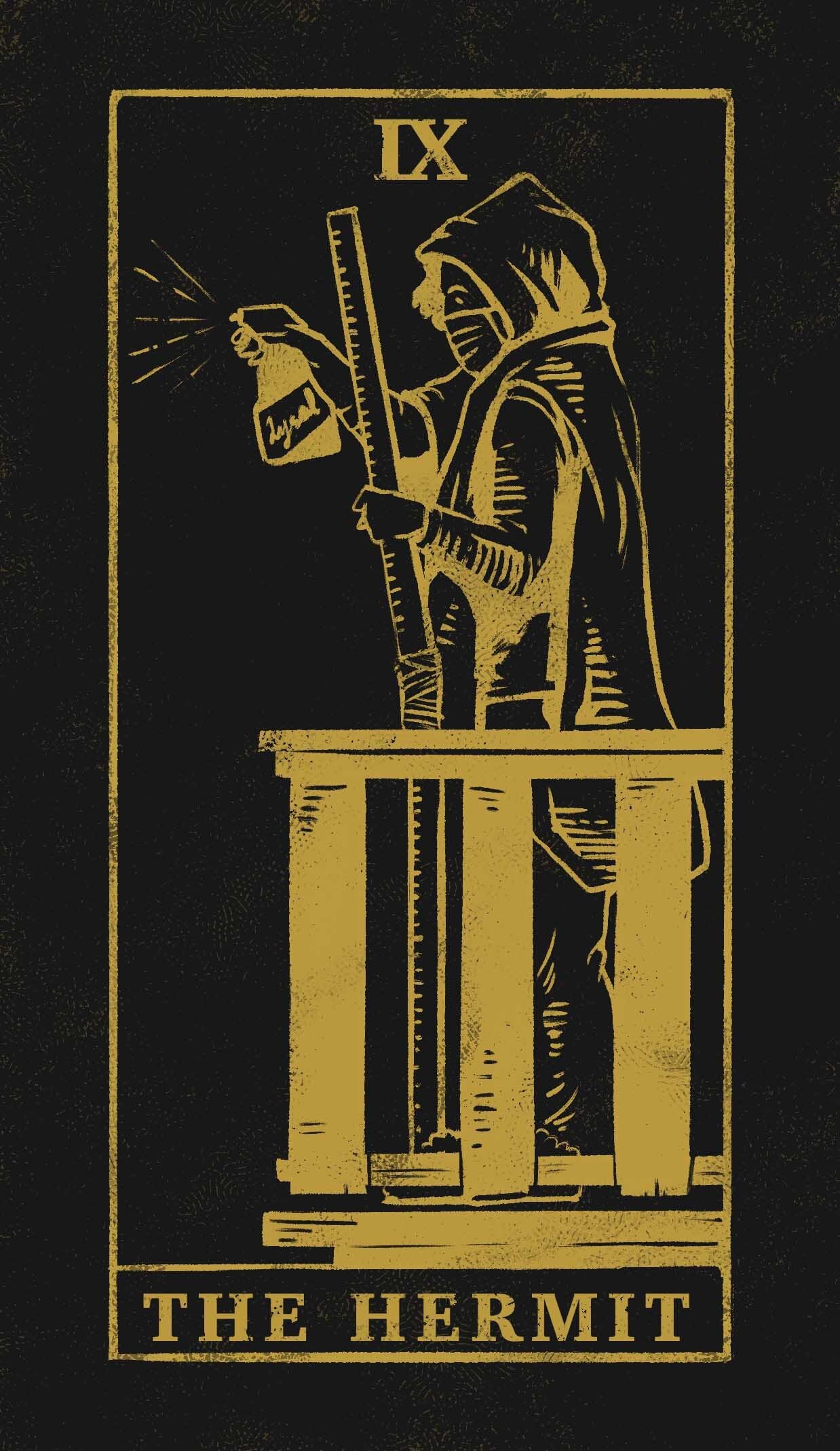

On March 12th, 2020, the University of Chicago announced that it would be suspending in-person campus activities for spring quarter in response to the COVID-19 global pandemic. This announcement came at a time when organizations from small businesses to cities and states were making the decision to implement work-from-home and stay-at-home orders to prevent the spread of the virus. The result has been a shift in how we relate to one another unlike anything in at least the past decade.

The arts field faces many questions as the situation continues, but perhaps one of the most significant is this: How do we relate to each other in this new world? How do we spend time together? How can we help fill the gap left by in-person interaction — and what new ways of interaction can we devise?

Platforms from social media to the Nintendo Switch to online streaming services like Twitch continue to offer answers to these questions through innovative ways of creating and sharing content, such as educational TikTok videos, the video game Animal Crossing: New Horizons, or the Critical Role Twitch stream. And games, which increasingly dominated media prior to COVID-19, have only expanded their impact in a time when many of us can’t actually see each other. Games offer what we’re craving in this moment more than ever: a sense of purpose and community organized under a shared goal (and fun ways to spend your time).

Take the example of Animal Crossing: New Horizons. On March 20, Nintendo released the game on the Switch — a launch that aligned with many of us being confined to our homes. While other companies reported staggering losses, Nintendo sold over 21 million Switch units over the year; Animal Crossing: New Horizons alone sold almost 12 million copies and broke records for digital sales. In a time of heightened stress and anxiety, the game is largely stress-free, presenting players with opportunities to conduct mundane tasks in a pleasant environment. And the game includes a social element in which players can interact and visit each other’s islands (as well as play the Stalk Market).

Assembling a transmedia story played and built by multi-generational teams, the group behind A Labyrinth is harnessing new media’s capacity as a potent social facilitator. This innovative approach to alternate reality games combines online engagement with personal relationships and offers crucial opportunities to connect in a moment of social distance.

What is an Alternate Reality Game?

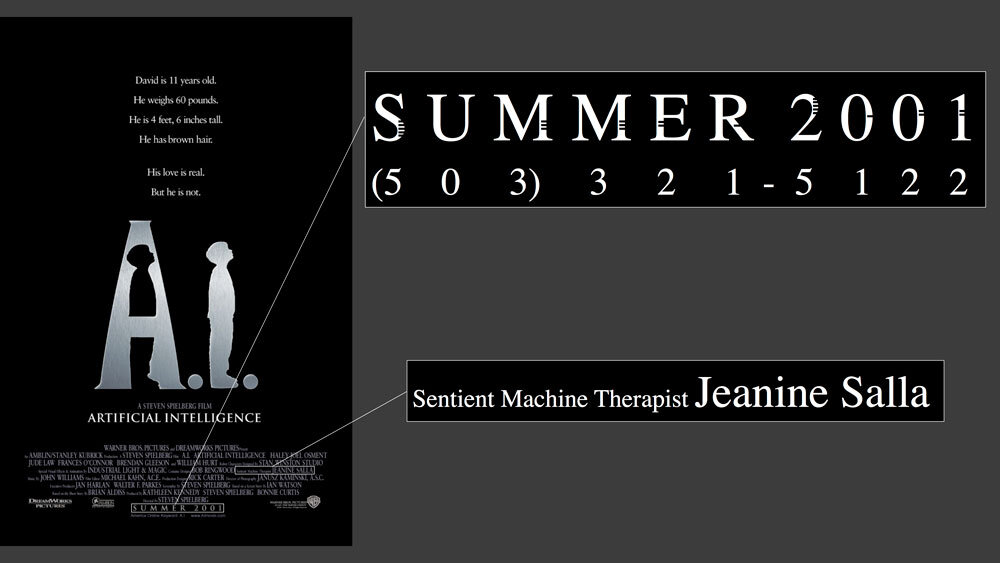

The Beast began with clues hidden in the movie poster for Artificial Intelligence.

Traditional games use discrete, constructed platforms as their setting: these platforms can be anything from the gameboard in Sorry! to the Xbox One. In alternate reality games, or ARGs, the platform is the world around you. The fiction is layered onto (and entwined with) the real-life infrastructure beneath it — and often the game asserts itself as reality. Indeed, most ARGs hold to the tenet of “This is not a game” — a phrase originating from The Beast, considered by many to be the first ARG — blurring the line between fiction and reality.

ARGs tell a story through multiple artistic and media forms, including (but emphatically not limited to) websites, video recording, live theater performance, email, social media, cryptic posters, and phone calls. Through this transmedia experience, players interact with the game and directly impact the course of the story through their actions and ideas. They are encouraged to solve puzzles, investigate mysteries, and communicate with other players to progress through the game. Players share information and expertise over a diverse range of challenges — and even sometimes push back against the boundaries of the game world.

“I think it’s the most exemplary art form for a moment of 'post-truth' politics and transmedia network culture,” said Patrick Jagoda, UChicago professor, co-founder of the Game Changer Chicago Design Lab, and co-director of A Labyrinth. “Alternate Reality Games are absorptive in the sense that they combine any other art form that you can imagine. There are visual components, audio dimensions, interactive elements. There’s live performance and video game mechanics. You can incorporate anything from email to TikTok in terms of puzzles or participatory opportunities. ARGs have a Frankensteinian hybrid structure that offers experimental ways of exploring and intervening in our contemporary moment.”

While ARGs share some characteristics with role-playing games like LARPs (Live Action Role Plays), they differ crucially in their relationship with the fiction of the world. In a LARP, players consciously enter a fantasy, playing a different character in a different world. In an ARG, designers integrate the puzzle into the real world and assert it as reality. Players progress through the game as themselves, and by doing so, assert the fictional world as in some sense real.

The Lab Team

The core group behind A Labyrinth is variously referred to as “the coven” and “the Council” — alluding to the role of a “puppet-master” in many ARGs — and, somewhat more officially, the Fourcasters. The Fourcast Lab originated during a prior UChicago ARG as an interdisciplinary group of faculty in possession of the “SPORE device,” which allowed them to communicate with not-so-distant futures. The continuing team that operates under this fictional title includes Heidi Coleman, Marc Downie, Patrick Jagoda, Ashlyn Sparrow, Kristen Schilt, and a team of interns. “Sometimes I think of us as a loose collective of misfits from different backgrounds that meet in this new creative process,” said Coleman, Senior Lecturer in TAPS and co-director of A Labyrinth. Their credentials are as varied and impressive as the game itself and range from immersive games, computer programming, and cutting-edge digital art to theatrical dramaturgy, the study of gender and sexuality, and transmedia storytelling.

Heidi Coleman, Marc Downie, Patrick Jagoda, Kristen Schilt, and Ashlyn Sparrow

Established in February 2019 as part of the Media Arts, Data, and Design (MADD) Center at the Crerar Library, the mission of the Weston Game Lab (WGL) is to foster a space on campus for the research and design of groundbreaking games. Under the leadership of Jagoda, the WGL has led directly to the blossoming of gaming-related initiatives through a variety of workshops, lectures, open-houses, and symposia. The University currently offers a minor in Media Arts and Design, but the bulk of the innovative new media work takes place through MADD Center and the WGL.

Supported by the College and the WGL, the team behind the Fourcast Lab facilitated this project and past ARGs (including Terrarium and A Labyrinth). Ashlyn Sparrow works as the WGL’s assistant director to develop games, interactive learning experiences, and digital media art. Sparrow supports projects that evolve the arts and design conversation that UChicago is now joining — and ARGs are a crucial aspect of that conversation. “We’re always interested in running experiments and thinking about experimental games [...] and how they can be different from your traditional screen-based video games or even tabletop games. How does performance interact with this, but it’s different from LARPing? How does live cinema interact with that, but it’s different from something like ‘Bandersnatch’ [the interactive Black Mirror episode] on Netflix? We’re really interested in looking at these different media forms and trying to think about something new.”

With Sparrow and Jagoda at the WGL, Sparrow said, the team will always be working on these innovative projects — projects that are “a little bit stranger, a little bit weirder.” A Labyrinth is the latest step in their quest to build something new.

The Path to A Labyrinth

The team behind A Labyrinth is not new to the world of ARGs: the Fourcast Lab has previously developed multiple UChicago initiatives in this form. Their most recent credits include the parasite and Terrarium, games that use collaborative play to disseminate information, build skills, and crowdsource solutions.

“This feeling of embeddedness or distance matters deeply, as students who do not feel welcome on campus are more likely to experience mental health issues or to leave campus.”

The first ARG crafted by the team, the parasite, was designed for the orientation of first-year students in 2017 and focused on developing a wide range of skills: collaboration, leadership, inclusivity, digital media, and twenty-first century literacies. In University student climate surveys from recent years, there has been a disparity in student experience, said Kristen Schilt, professor of sociology and director of the Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality. “Some students [are] reporting a sense of belonging and others [are] reporting experiences of alienation and discrimination,” said Schilt. “In particular, LGBTQ students, students of color, and first-generation students report a greater sense of social distance on campus starting from the first day they set foot on the grounds. This feeling of embeddedness or distance matters deeply, as students who do not feel welcome on campus are more likely to experience mental health issues or to leave campus.” For Schilt and the Fourcasters, simply teaching students to be aware of diversity isn’t enough — they were looking for more creative ways to intervene.

Funded partially by the Neubauer Collegium, the game created a robust play experience for incoming students as they sought to investigate a century-old secret society at the University. All told, the game ran from May to September 2017, involved approximately 1,750 people, and utilized nine site-specific challenges as well as multiple online platforms. Its significant live component utilized actors, designers, writers, and performers from UChicago as well as First Floor Theater and Chimera Ensemble (theater companies started by UChicago alumni) in interactive performances.

“That ARG convinced me that worldbuilding is electric when it allows players (or an active audience) to impact outcomes,” said Coleman. “That’s more than a ‘choose your own adventure.’ It’s thrilling to create a world that takes on a life of its own based on players. That kind of agency is productively radical in my mind.”

In 2019, the team created Terrarium, again for first-year students, which was built to focus on the interdisciplinary problem of climate change. Via services including Twitch and Open Broadcaster Software, the ARG utilized live streaming, live-action performance, video game mechanics, and puzzles to create a mixed-reality story. Players were tasked with helping performers get out of “inverse escape rooms” via multimedia interactions and shared information. The ARG recruited faculty and staff from across the humanities, sciences, and social sciences and culminated in the Futures Design Challenge, a pitch session in which students put forward ideas on how to combat and mitigate climate change.

Into the Maze

Fresh off of Terrarium, the team was thinking about future orientation games when they were faced with the unexpected challenge of a campus community entirely, well, off-campus. “It was this question of, we managed to successfully engage the incoming class for orientation with Terrarium,” said Sparrow, “And it was done all online. How can we do that again for these UChicago students who essentially have been pushed off of campus — how do we make people feel connected to their community, to their campus, through the use of the game?”

Due to the circumstances, the game was developed on a rapid development schedule, one much briefer than that of prior games. “The moment that we realized what was happening with COVID-19 in mid-March,” said Jagoda, “We had a team meeting and basically said to ourselves, we’ve been working on issues of online education and large-scale mobilization of students and UChicago community members for so many years now. This seems like a situation in which that work becomes even more urgent, but we should also help build community for students. At the very least, we wanted to create a platform where students could reconnect to one another and also put their creativity on display.”

For projects like these, the typical runway is upwards of six months — the parasite was developed over the course of the year prior. A Labyrinth was constructed in just a few weeks.

The initial idea was developed in a sprint during Reading Period of Winter Quarter, said Coleman. They developed the story structure — a minotaur in a labyrinth — over the weekend. The team initially planned to use the interior of several buildings, including the Logan Center and the Regenstein Library, to form the architecture of the maze. Unfortunately, it soon became apparent that wouldn’t be possible, as access to interior spaces was heavily restricted. The team was able to adapt the story and technology to use the outdoor spaces of the UChicago campus and filmed hours of footage of the minotaur (known in-game as the Taur) traveling between campus buildings. With crucial assistance from Master of the Humanities Christopher Wild, they launched the game on April 6th. All told, the development took less than three weeks.

“This was one of those situations where we were acting like a design-slash-artist collective,” said Sparrow. “We have a problem, we have all our skill sets, and we can work together to make this happen. And we worked with each other before, so we trusted one another. It’s just being able to hit the ground running.”

We wanted an allegorical narrative about helping one another come back home and about what it means to return to and rethink a home that’s been transformed.

— Patrick Jagoda

While there are limits to what can be achieved in such a short time frame — for example, the team would usually apply for grants, something they couldn’t do this time — the game ran fairly smoothly from a player perspective. Using their past experience with ARGs, the team rapidly deployed the website and wrote more than 140 quests. The swift development is a testament to the group’s collaboration, said Jagoda: “Because this team has worked together in stressful situations, we believed that a core team of four or five people who knew each other’s work habits really well could be responsive, even in an impossibly short time frame.”

The original idea involved a library with four golden books, each leading to a different Twitch room with a different character. The library idea led them to the concept of a labyrinth, which in turn spurred the creators to bring in the character of the minotaur. Using the Greek story gave the designers access to a well-known mythology and a recognizable game narrative, significant assets when devising a game this complex. And the Taur is an ideal protagonist for a game centered around solving puzzles.

With the foundations established, the Fourcast team took the original story and ran with it. Rather than casting the minotaur as the guard of the labyrinth, A Labyrinth set the goal of helping the Taur return to their home in the center of the maze. And unlike the menacing figure of legend, the Taur is communal, inviting, and shy, and needs the assistance of the players to return from exile.

The story was intended as both a lighter version of the original and an allegory for our current moment. “Most of us have been disconnected physically from the University of Chicago campus, which is a kind of home,” said Jagoda. “So we wanted an allegorical narrative about helping one another come back home and about what it means to return to and rethink a home that’s been transformed.” By playing the game in an altered version of the UChicago campus, players entered a liminal world that reflects our current shared reality.

Down the Rabbit Hole

“The narrative is supposed to be enjoyable and weird, as opposed to puzzling and revealing. [...] It’s a reflection of the brief that we gave ourselves, which is — you know, the students have lost so much. And we’re just going to try and restore, or maybe exchange, a little bit of that.”

ARGs traditionally begin with a “rabbit hole,” terminology based on Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Like Alice, participants in ARGs travel through a portal into an entirely different world. Often these entry points take the shape of something a little strange in the real world that — if someone is paying close enough attention — can lead them into the world of the game. In prior games, the team has worked to make this initial interaction subtle and uncanny, beginning the game in a way that casts doubt on its fictional nature. For A Labyrinth, however, they went in a different direction. “We didn’t want to be quite so secretive for this project,” said Jagoda, “We basically figured, there’s enough uncertainty and paranoia in the world right now. The way things are going, let’s relax that aspect of the ARG form and say, ‘Hey, this IS a game. Come play our game, everyone is welcome.’ [...] I think something that people need right now is clarity, community, and playfulness.” Marc Downie, a digital artist and lecturer at the University who first joined the Fourcasters in fall 2019 for Terrarium, agreed. “The narrative is supposed to be enjoyable and weird,” he said, “As opposed to puzzling and revealing. [...] It’s a reflection of the brief that we gave ourselves, which is — you know, the students have lost so much. And we’re just going to try and restore, or maybe exchange, a little bit of that.”

The initial email from Fourcast Lab. Image courtesy of Ashlyn Sparrow.

Working with Sandy Weisz from the Mystery League, the Fourcast Lab built the initial puzzle. On April 6th, an email from the College went out to the broader UChicago community (including alumni and Lab School students). The email included a barcode that, when scanned, led the player to a website with a scrolling green bar. As more individuals accessed the page, images appeared — pixelated renditions of notable UChicago buildings. After 3,300 unique visitors accessed the page, the full slate of buildings were unlocked (you can scroll through the revealed buildings here) and the next step in the game was available. Once a key phrase was decoded — “the labyrinth is the Reg” — participants received a formal introduction to the game. Overall, more than 3,500 people participated in the initial puzzle.

The launch wasn’t without its share of challenges. “This is where, when you do things very quickly, things break really quickly as well,” said Sparrow. “But also, when running an ARG, you have to be very flexible and be ready for almost anything. We had three different camps of people: one camp observing what was going on, not really actively participating. Another group of people who were actively trying to solve the puzzle itself. And then a third group, who are my favorite group, because they cause the most chaos for me. And those are the people who are like, ‘You know what, I’m just going to try and use technology to hack this website.’”

Participants had about a week to sign up and form teams via Slack. In total, 73 teams participated, with groups ranging from current undergraduates to graduate students to Lab School students to alumni. And then the game began.

A Labyrinth in Practice

As per the history established in Terrarium, the Fourcast Lab informed players that the Lab could communicate 30 years into the future and had access to the “SPORE device,” enabling communication over time with different realities. This time, they reached out to Labyrinth, a central transportation hub of portals that connected space-time nodes including the intermittently appearing parasite room from the parasite and the four versions of 2049 from Terrarium. A creature called the Taur was wandering this world — an alternative space-time located approximately on the UChicago campus — and needed the players’ help to reenter its home in the Regenstein Library.

The players were tasked with completing a diverse range of objectives. The primary goal was a collaborative one: all of the teams had to work together to help the Taur get back into its home. During this main quest, the players interacted with the Taur as they voted on where to send them across the altered campus. This endeavor occurred over a series of Hub Quest discoveries held on a Twitch feed (available here). Compiled from the video footage taken on campus, the stream adapted in real time as players voted on where to send the Taur, evoking media forms like Choose Your Own Adventure books. Unlike that format, however, the world of the Labyrinth was conveyed primarily through video and shaped by collective interaction. At each of the four hubs — Cobb Hall, Rockefeller Chapel, Henry Crown, and the Logan Center — players unlocked one of the Hub Quests, which were worth the highest number of points.

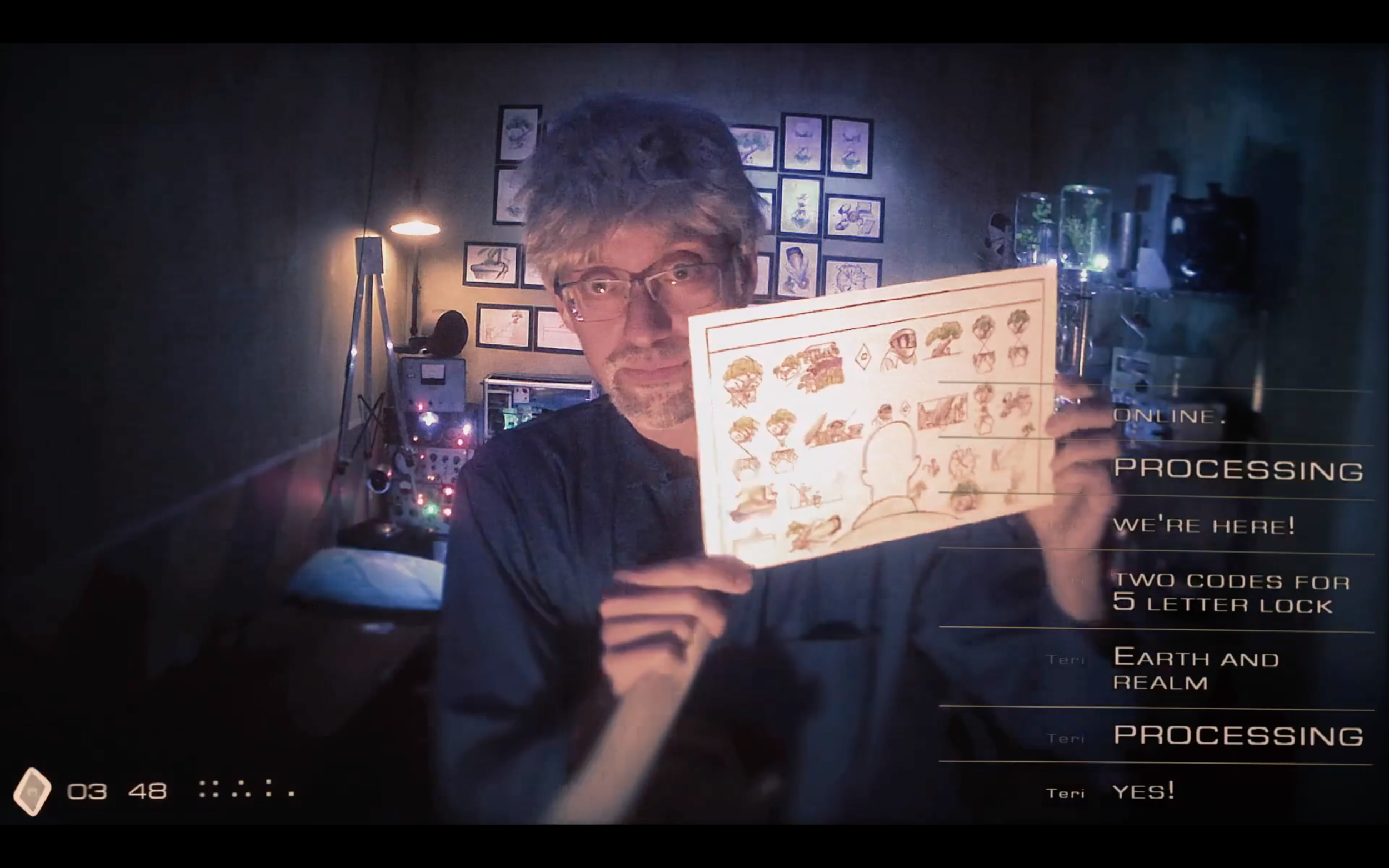

Christopher Wild offers the Taur a hammer. Image courtesy of the Labyrinth Twitch stream.

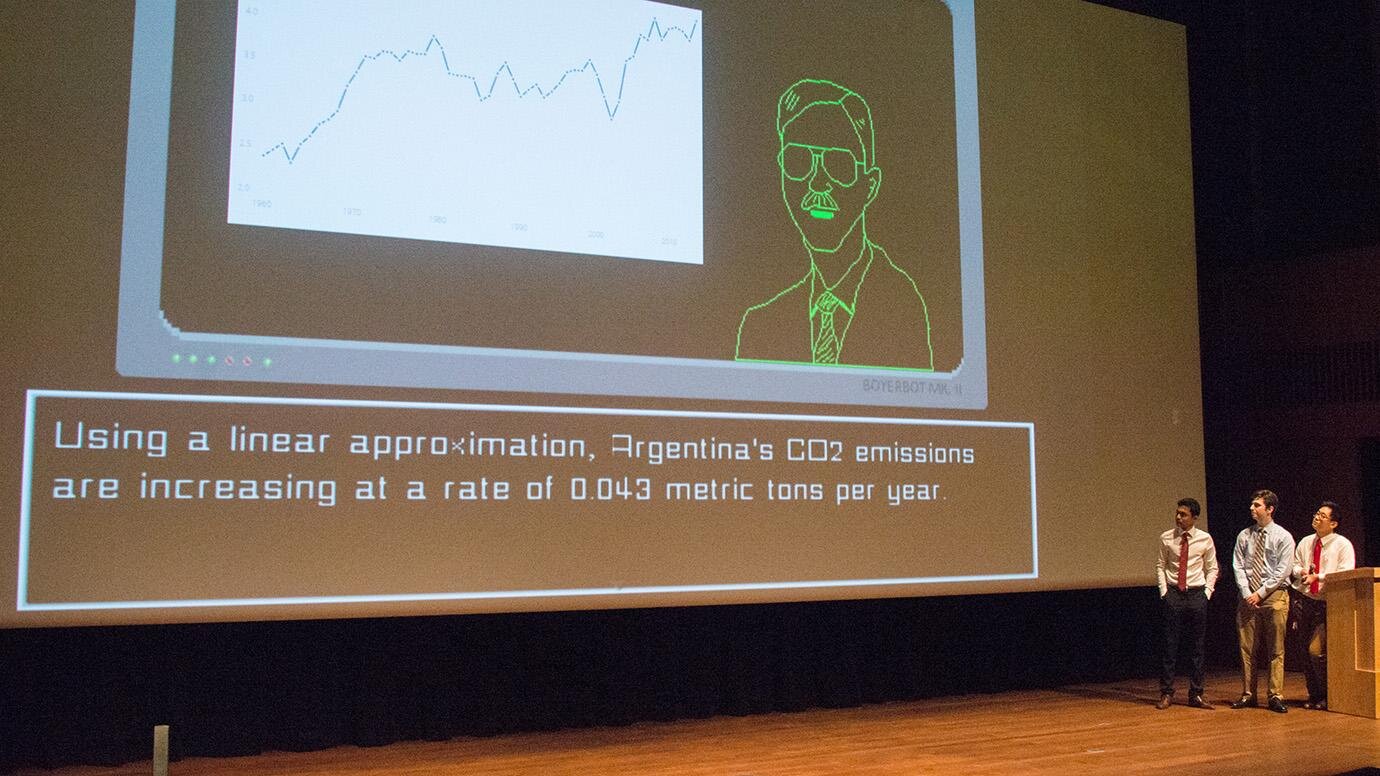

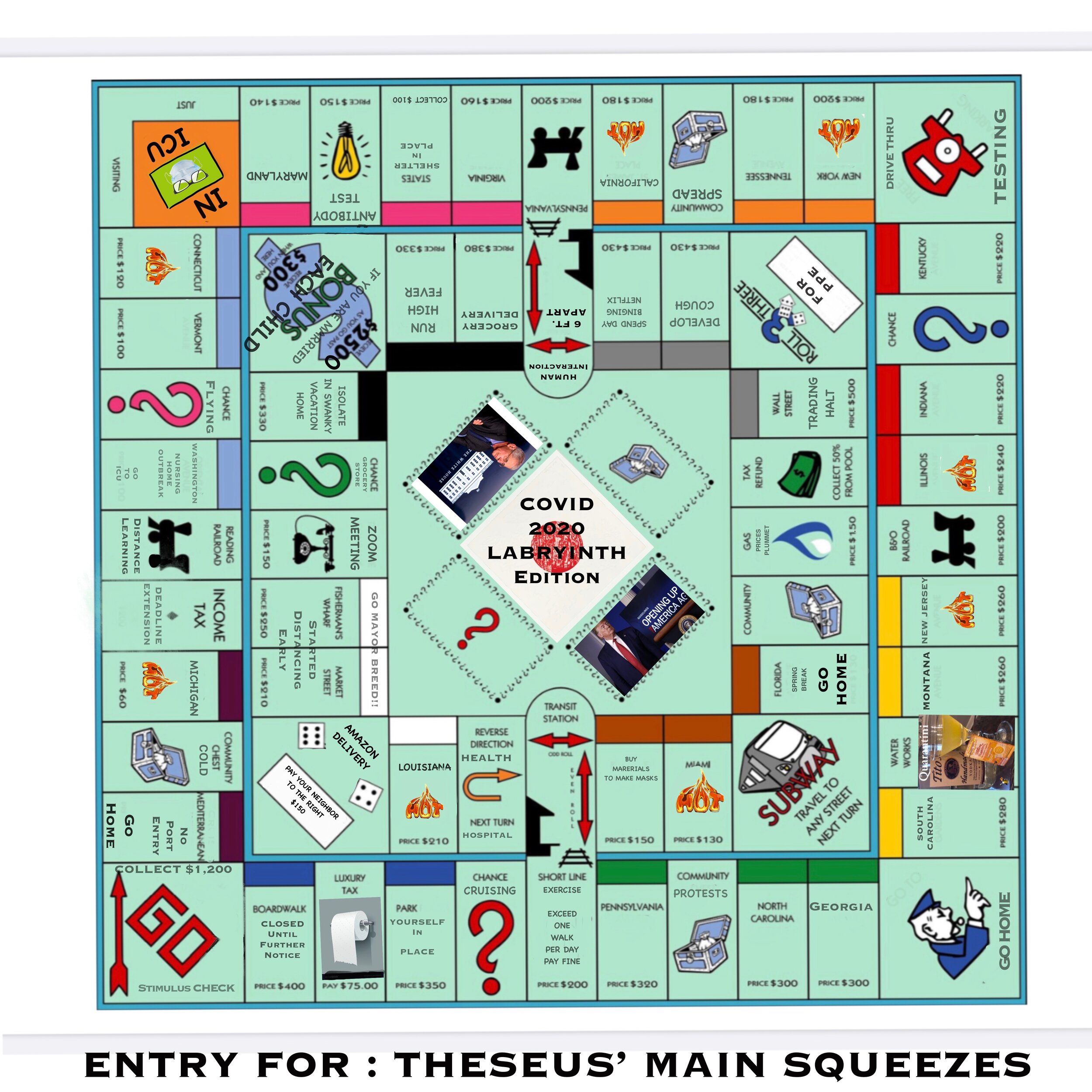

In addition to these weekly cross-team collaborations, players earned points through side quests published on the Fourcast website. The quests fell into seven different categories — connecting, solving, making, playing, worldbuilding, moving, and researching — designed to appeal to different types of gamers and game players. For example, Solving Quests were specifically puzzles with one right answer. Playing Quests asked the player to participate in another game (for example, play the board game Pandemic with other participants via Zoom). Researching Quests tasked players with researching and producing a specific type of knowledge. And Worldbuilding Quests allowed players to speculate about the world of the game, utilizing elements of speculative design, creative writing, and policy research.

Finally, there were Object Quests, which were unlocked based on how well the players helped the Taur navigate the Labyrinth via Twitch. As the Taur walked through campus, players could find objects, which would then open specific quests on the website. For example, a quest called Tenacious Tool was unlocked when players encountered Christopher Wild on the Twitch stream. Wild gave the Taur a hammer, and a quest was unlocked that asked the players to build a marble labyrinth game out of cardboard (for bonus points, it could be a map of A Labyrinth itself). In another example, Professor Agnes Callard handed over a small owl statue (alluding to her Night Owls series) that unlocked the Bird Bust quest.

The UChicago campus has proved to be a potent resource for players accessing it from afar. “We’re in a very odd situation because we’ve got the campus that the students know really well,” said Downie. “It’s a fairly dense campus. It has lots of landmarks in it. It’s meaningful. What other setting is so potent as this campus, so recognizable, so familiar to your audience that you can manipulate it somewhat?”

At one point, the virtual campus was flipped from left to right, making it difficult to tell if the Taur was navigating north or south. The altered space-time of the Labyrinth was suddenly different from the reality of the campus — but this new reality of the game allowed players to continue to push forward and engage, learning more about the altered world as they did.

The final Top 10 leaderboard. Courtesy of Fourcast Lab.

Quests also engaged notable members of the UChicago community, from Fourcasters to academics like Lauren Berlant to Dean John “Jay” Ellison (check out the list of Labyrinth Dwellers here and at left). These individuals offered tools, guidance, and information as the Taur made their way home — and offered students a way to engage with familiar figures of the campus community.

Overall, A Labyrinth involved 73 core teams who completed just under 1,000 discrete quests in four weeks, earning a total of 1,128 quest points. As of the final count, The Oracles took first place with 142 points, followed by Powered by Pikachu, #Cazoo-Cids-Choir-Loves-Mustard-Green, and BrainCells (see the full Top 10 leaderboard here). Each member of the top four teams received $75.

The top team, The Oracles, is a family with students at the Lab School. “We pooled our money and have started a list of what we might like to spend it on,” says The Oracles’ captain Shane Halbach. “So far ‘a pet’ seems to be a top contender, but I’m not sure about that.”

Players solved, sang, coded, crafted, built, and invented their way through a transformed campus in a mode of interaction that not only helped fill the gap left by in-person interaction, but provided a new model for virtual engagement in times of stress.

New Technology

A Labyrinth developed powerful new software, but it also made extensive use of existing proprietary software like Twitch and Slack. Teams formed and coordinated via Slack channels and used the service to discuss across teams. Sparrow functioned as a sort of community manager, monitoring Slack in order to field questions and determining point allocation from submissions. “Like a hidden-in-the-back Wizard of Oz type,” she said.

The A Labyrinth Twitch channel.

The weekly interactive video streams took place over Twitch, an online service that is dominated by video game livestreams but also offers content including musical and creative broadcasts. Crafting a live transmedia narrative over Twitch is a new idea — one pioneered by the Fourcast team. For Terrarium, Downie developed a novel digital infrastructure that integrates video clips with Twitch streams. The system has the capacity to replay, manipulate, and distort premade video clips according to user interactions before sending it back to Twitch in real time. This means that player decisions can directly affect the virtual world, essentially forming a video game-like engine. Connected to Twitch, it converts premade video into an interactive playspace.

The team was able to use this resource again for A Labyrinth but faced the challenge of lacking interior spaces. That meant they had less control over the setting — but nevertheless, after filming hours of footage, the outdoor maze proved to be a workable setting for this technology as well.

Individual quests further integrated technological aspects in line with the “Frankensteinian” aspect of the ARG medium. Quests asked users to create a coordinated Zoom call, build a fort in Fortnite, create a song and dance on TikTok, and create a maze through Rockefeller using the interactive fiction web tool Twine (check out submission highlights in the Labyrinth Showcase).

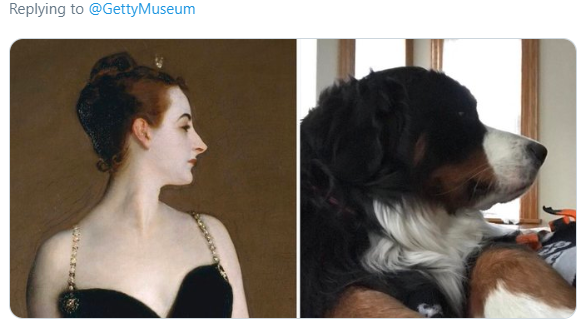

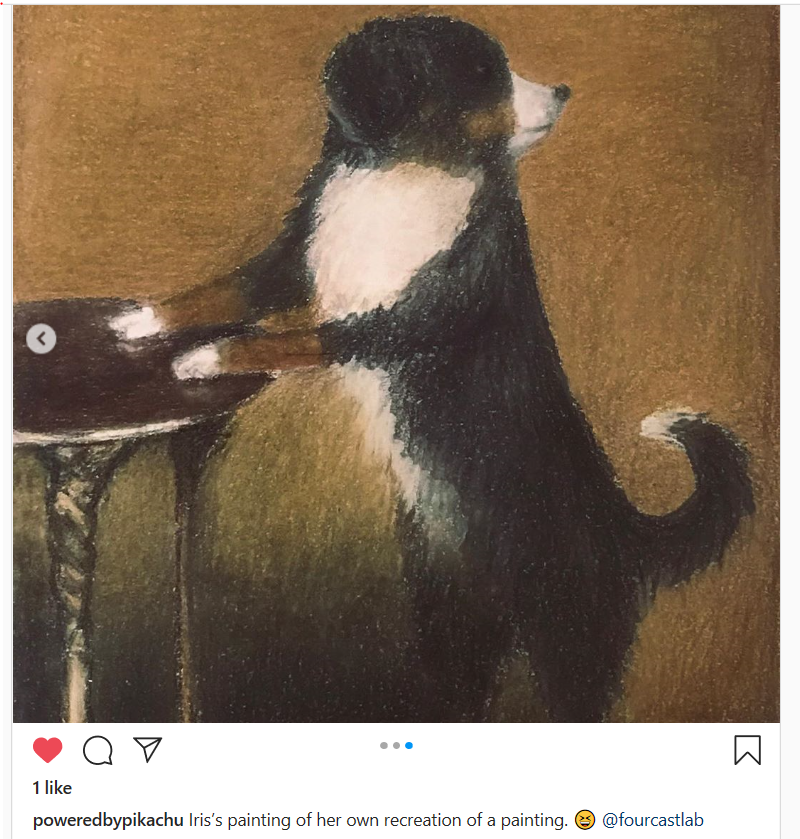

“I loved them all, despite them being so different,” said The Oracles’ Halbach of the quests. “How can you compare writing and performing an entire musical to planning a heist, or creating a TikTok dance to having a fancy tea party composed only of apocalypse-style, shelf-stable food? How do you compare teaching myself to juggle with taking a photo of ourselves recreating a famous painting, and then painting our recreation in the style of the original painting? You can’t, and that’s my favorite part!” The diverse spate of quests offered opportunities for all team members to showcase their abilities or get out of their comfort zones.

The key to the multimedia aspect of ARGs is the mystery they offer. “In interviews with students who have participated in our ARGs,” said Schilt, “The sense of wonder and magic came up again and again. [...] Finding a rabbit hole and getting into an ARG can make the rest of the world feel magical, too – is that word misspelled on a flier a clue or just poor editing? Is that QR code pinned to the bulletin board for you? This kind of fun/paranoid thinking transforms the everyday into something always on the brink of potential excitement. And, unlike many forms of paranoid thinking, ARGs provide a community where people can work out clues together – and share their excitement. It is this collaborative element that I think really makes this form of media special – particularly in this moment of losing in-person interactions.”

In Person, At A Distance

A Labyrinth provides a model for utilizing emergent and new media in building community. The 73 teams were intergenerational and multi-location: in addition to UChicago undergraduate students, MA students, and alumni, game participants include a top-performing team of sixth-graders at the University’s Lab School and parents in the Chicago suburbs. In a time where the conventional means of establishing personal connection are increasingly strained, the digital creativity, competition, and teamwork fostered through A Labyrinth offers an opportunity to build new ways of relating to each other.

Creative work is the best way I know how to deal with helpless realities. If you act as if something is real, it becomes so.

— Heidi Coleman

Team #1 (which finished in fifth place) was made up of postdoctoral students and professors in various stages of their careers. They found A Labyrinth to be a place of connection and entertainment in isolating times. “We didn’t really know what it was,” said team captain Sarah Outland. “We were like, this is a good way for us to just have a thing to do to stay in touch during all of this. [...] And we definitely did have fun. I think a lot of us are people that were hobbyists of various varieties. So for us it became a cool challenge of like, how are we going to make this thing? Or like, who’s got what in their house that’ll make the funniest version of XYZ thing?”

It also provides insights into the practice and product of art: like much of our digital world, the game is ephemeral, lasting only a few weeks. But its lasting products are evident, both in the player-created content and the lasting personal connections.

“It’s a really nice community of folks, because we opened this up not only to UChicago students… but also for undergraduate students and staff and faculty and anyone connected to the UChicago community. So Lab School students and the parents and families of UChicago students,” said Sparrow. “Actually the folks that have been the most active are the folks who are families and grad students and Lab School students. [...] That’s amazing.” And the teams have formed strong social bonds over the course of the game, facilitated by the joint creativity required for the endeavor. Since many of the quests were open-ended, Sparrow added, “You can see people’s creativity and how they decided to come up with team names, how they’ve decided to produce a solution for a quest, the camaraderie between team members.”

Team #1’s famous cactus. Image created by Melissa Osborne, courtesy of Sarah Outland.

The top two teams — The Oracles and Powered by Pikachu — got to know each other by following their A Labyrinth Instagram accounts. For one of the quests, Team Trivia, teams received bonus points for swapping games with another team. “At one point [Powered by Pikachu] contacted us and asked if we wanted to trade, just a few hours before we would miss our chance for the bonus points,” said Halbach. “We wrote, I think, 200 questions over the course of three or four hours and finally sent it over to them minutes before the deadline!”

Creativity, absurdity, and humor were very much on display in the teams’ submissions. “One of my teammates had this very tiny cactus in her home,” said Team #1’s Outland, “And the cactus almost became our mascot. So anytime there was a quest, we’d be like, can we use the cactus for this? [...] The cactus was probably in like ten different challenges. [...] One of them, we had to make a propaganda poster. And so we used the cactus. It was like, ‘The cactus is always watching you.’”

A Labyrinth provides a new model of interaction, combining the media and collaborations of our digital world into something more. It brings together theater, online gaming, visual arts, and puzzle-solving and integrates the specialities of artists, designers, technicians, gamers, coders, teachers, and others. And it provides an open-ended collaboration space for self-made teams that adapt the given structure into whatever they want it to be. “Our players knew that there wasn’t really an alternative world. But they were being given the option to suspend disbelief and to embrace the ‘what if,’” said Schilt. “For me, it is reminiscent of some of the good parts of childhood — the willingness to ‘yes/and’ situations and thoughts that, as an adult, you become less open to.” And while media like novels or film strive for the suspension of disbelief, ARGs work towards a more active “production of belief.” “The shared world becomes real, if only temporarily, for a collective that co-creates and inhabits it,” said Jagoda.

It’s evident that games and gaming are a powerful medium in our contemporary world, made even more so by the demands of the current pandemic. In a world where diverse media is readily available and juggling many responsibilities in the norm, A Labyrinth provides a media format that’s not only satisfying but productive. “Creative work is the best way I know how to deal with helpless realities,” said Heidi Coleman. “If you act as if something is real, it becomes so.”

“We’re not saying that games are the solution or the panacea for your problems, but we do think that games are a great place to think through certain problems and have people come to their own conclusions.”

But the goal of ARGs like this one goes beyond gameplay. “We’re interested in social impact and thinking about games that feel fundamentally different from the standard educational game affair,” said Sparrow. “We’re not saying that games are the solution or the panacea for your problems, but we do think that games are a great place to think through certain problems and have people come to their own conclusions, which is why our games operate the way that they do. We’re not here to tell you what’s right or what’s wrong, but we do want you to be critical about how you feel or how you’re thinking about a specific problem.”

What Comes Next?

The team is already looking towards the future, planning more complex stories and fine-tuning the technology. “Every time we develop, there’s a sense of something we could do ‘next time,’” said Coleman. “Halfway through Terrarium, I started to say ‘in 2.0.’” For the next project, Downie is interested in blurring the lines between live and pre-recorded video, allowing the players to transition seamlessly between the two. “It would be wonderfully disorienting,” said Downie. “We’re getting to feel like we’ve discovered something and figured half of it out. What’s the real version of this? [...] I don’t know what that is yet, but we still have energy and enthusiasm to figure it out, that’s for sure.”

The team is also thinking about new audiences. A Labyrinth expanded the player base established in the parasite and Terrarium beyond UChicago students, engaging alumni and Lab School students with great success. Based on the involvement of the Lab teams, Coleman is interested in building an ARG for a middle school audience, exploring an age at which many people are transforming their identities. “Role playing games, like performance, allow players to be fluid in exploring identity,” she said. “In ARGs, the players have the transformative platform that actors do in a scene study class.” Team members including Sparrow and Jagoda previously worked with Melissa Gilliam, co-founder of the Game Changer Chicago Design Lab, on past ARGs aimed at 14-18 year olds. These games — The Source (2013) and S.E.E.D. (2014) — took on STEM learning among underrepresented youth, highlighting the potential of ARGs to address structural social issues.

It’s too soon to say how exactly COVID-19 will affect the art field at large, although changes so far have been sweeping and severe. Theaters and museums have closed their doors, with many postponing or canceling upcoming shows, exhibitions, and seasons. As frightening as these developments might be, it also offers an opportunity to embrace new modes of storytelling — and by extension, new ways of connecting to each other. “The sciences are leading impressive efforts to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 in so many different ways,” said Jagoda, “But I think the humanities and the arts can also make contributions in precisely the areas of community building, experimentation, formal innovation, reflection, and playfulness, all of which I hope this game contributes to in a modest way.”