Contemporary art collection grows at Booth School of Business

Installation view, work by Andre Butzer

By UChicago Arts

If you are looking to see cutting-edge contemporary art at the University of Chicago, you may be surprised that the Booth School of Business should be among your top destinations. The school’s now 13-year-old collection includes more than 500 artworks by 150 emerging and established contemporary artists such as Paul Chan, Tacita Dean, Cao Fei, Raymond Pettibon, and Wolfgang Tillmans.

Art to be lived with; art to inspire inquiry; and art that facilitates intellectual curiosity are core tenets of the Booth collection. Canice Prendergast, W. Allen Wallis Distinguished Service Professor of Economics, spearheaded the founding of the collection, and continues to steward these ideals today. Prendergast joined Booth’s faculty in 1990 and became known among his colleagues as an arts connoisseur; after the school moved into the Rafael Viñoly-designed Harper Center in 2004, he was asked by the Dean to pick artwork for the school’s new state-of-the-art home.

Penone tree sculpture. Courtesy UChicago Booth School of Business.

Presented with this opportunity, Prendergast chose to convene a five-member steering committee comprised of a mix of art world professionals and Booth stakeholders. Since then, the committee members have been made up of James Rondeau (then curator of contemporary art, now President of the Art Institute of Chicago), Suzanne Ghez (then director of the Renaissance Society, now Adjunct Curator at AIC), Suzanne Deal Booth (art conservator, philanthropist, and collector), Dean Valentine (art collector and alumnus of Booth), and Prendergast. When members consider new artwork, four out of five have to vote “yes” in order for it to be purchased for the collection. In this manner, the committee has added an average of twelve to fifteen new artists to the collection each year. Tillmans, a German photographer and installation artist, was one of the first high-profile artists whose work became part of the collection. He appreciated the fact that the works purchased for the school would be displayed in well-trafficked public spaces, rather than sequestered in storage—frequently the fate of art purchased by private collectors.

Installation view, work by Matt Mullican, Olivier Mosset.

“The collection is contemporary, as befits the architecture of the Harper Center, but does not have a single theme,” the Booth’s website states. “Instead, it reflects the mission of Booth and the University of Chicago, by including works that are sometimes conceptually challenging, yet raise important questions for our students, staff, and faculty.”

The acquisition of artworks in the collection has been funded through the generosity of the Booth family. To date, the selection committee has spent approximately $3 million to acquire more than 500 artworks. Almost all of the works purchased are on display in the Harper Center, as well as the school’s downtown Gleacher Center, and the newly opened Hong Kong Center, where Booth recently launched an Executive MBA program.

An Art Collection Focused on Inquiry

Jill Ingrassia-Zingales had been a marketing and design executive for twenty years when she decided she was ready for a change. She enrolled in UChicago’s Master of the Arts Program in the Humanities (MAPH) in 2016 and soon gravitated toward the Booth art collection as a potential focus for her Master’s thesis. Having first stepped foot into Booth a decade before, Ingrassia-Zingales noticed that the art collection had a steadily-growing profile. In recent years, curators from New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and visitors in town for EXPO Chicago have made the Harper Center a stop on their Chicago circuit.

On a day-to-day basis, Ingrassia-Zingales—a longtime arts lover who is on the boards of both the Smart Museum of Art and the Renaissance Society—observed that people were interacting with individual art objects, but did not have the opportunity to interact with the collection in its entirety. After she participated in an exhibition tour led by a senior curator at the AIC, Ingrassia-Zingales developed the idea of an archive for the collection. The curator had mentioned that she created a reference tool for herself, a catalog of the museum’s entire collection within a three-ring binder. “Once I realized how useful a reference source like that could be, I knew I wanted to create that for the Booth collection,” says Ingrassia-Zingales.

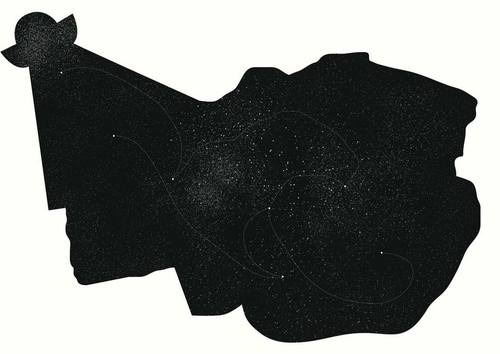

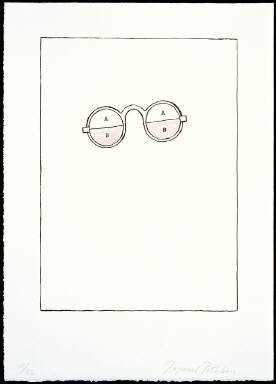

From L to R: Tussle, 2004, by Cao Fei; Untitled, 1998, by Raymond Pettibon; A free press (formerly Ursa Minor), Constellation Series, 2005, by Paul Chan.

In her thesis, “An Art Collection Focused on Inquiry: The Case for an Archive,” Ingrassia-Zingales argued that building an archive for the Booth collection would serve as the “stimulus that converts spontaneous observations about individual works in the collection into informed deliberation, thereby transforming the collection as a whole into an object of inquiry.” She organized records that had accumulated over the years, laying the ground work for a comprehensive catalog of the entire collection. The Visual Resources Center in the Department of Art History is now working with Ingrassia-Zingales and two other art history graduate students to create a digital repository of images documenting all of the collection’s works. Building off the collected records, the students are creating high-quality metadata records that will facilitate multiple ways of searching the online digital collection once it launches in LUNA (the Art History department’s image collection database). For example, users will be able to search by type of artwork, cultural context, material, subject, artist gender, acquisition order, and more.

“I’ve learned what thrills me about art,” Ingrassia-Zingales says of the experience. “It’s the conversations, the discussion.” The presence of the visual arts in the business school exposes its students, faculty, and staff to a different language of abstraction, one that prompts critical thinking, doubt, inquiry, and criticism. Ingrassia-Zingales believes that the collection owes its success to Prendergast. “[He] is the bridge, the person who can talk to the Nobel Prize-winning economists and the art world insiders,” she says.

Canice Prendergast.

Until recently, Prendergast personally wrote all of the wall texts for the artworks on display. Each quarter, he also offers a popular, regularly sold out tour of the art collection with Booth students. During a recent tour in late April, Prendergast highlighted many examples of idiosyncratic conceptual art from the collection, from Pope.L’s Trophy (a stuffed teddy bear slathered with peanut butter and paint) on the fourth floor to Giuseppe Penone’s Idee di Pietra (a trompe l’oeil tree made of bronze and steel, with granite stones nestled in its branches), installed in the outside courtyard. Prendergast shared nuanced insights on the challenges of collecting contemporary art and emphasized the essential importance of a collector’s reputation in today’s art market. Nowadays, he receives hundreds of emails from galleries interested to sell work to Booth. “We have a reputation similar to a museum,” he says. “People know that we don’t buy art in order to flip it for profit. When they come to see our collection, they can tell we know what we’re doing.”

A Resource for Curatorial Practice

Ingrassia-Zingales’s thesis inspired her advisor, Art History Professor Christine Mehring, and Prendergast to collaborate on providing hands-on curatorial experience to other students. With the impending launch of a curatorial option in the MAPH program, the Booth collection is poised to serve as a resource for curatorial practice. The business school recently expanded its offices to the McGiffert House (next door to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Robie House) and, as a result of this move, wanted to introduce art into the space. Three Art History students—Harry Choi and Maggie Hire (both MAPH students), and Elizabeth Smith (a fourth year major)–were invited to curate an exhibition at McGiffert.

McGiffert House. Photo by Tom Rossiter.

Working under the direction of Prendergast, Mehring, and the Smart Museum’s Associate Curator Jenny Carty, the students organized an exhibition called Small Frequencies, featuring 33 works from the Booth collection. As part of the curatorial process, the students organized the artworks by theme, generated introductory and interpretative wall text and material, and created an installation plan suited to the physical layout of the McGiffert House. The curatorial statement explains that the name of the exhibition came from Carrie Gundersdorf’s eponymous painting in the show, “in which the artist renders the natural phenomenon of light wave frequencies in beautifully abstracted swaths of oil on canvas.

The students were also given the opportunity to help select the newest acquisitions for the Booth collection, which include two large collage works by Sam Gilliam. “Gilliam is perhaps best known for his Drape Painting works [which] have been widely exhibited,” Smith says. “Being able to acquire these spectacular, large-scale collage works that the public may not be as familiar with, and which showcase the evolution of his practice, for the collection was very exciting for us.”

Maggie Hire and Harry Choi—students in the Master Program in the Humanities—and Elizabeth Smith, an undergraduate Art History student, put finishing touches on their Booth collection installation at McGiffert House.

Smith described the experience of selecting new works as illuminating, and the student curatorial team was interested in the representation of Chicago-based artists within the larger collection. As a result, they also incorporated works by Laura Letinsky and Catherine Sullivan—two artists who teach in the Department of Visual Arts—into the new exhibition.

Organizing the exhibition and engaging with the Booth collection has offered the students various insights into curatorial work. “When you think of curating an exhibition, you imagine that you’re going to have a blank slate, but in reality you never have a totally blank slate,” says Choi. Working with the specific parameters and physical constraints of McGiffert House turned out to be a productive challenge, one that reminded Choi of contemporary art curators organizing exhibitions in unconventional spaces, finding new and transformative ways to show artwork. With the McGiffert exhibition now added to his curatorial experience, Choi will start as the Marjorie Susman Curatorial Fellow at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art in July 2019. For Hire, working with the Booth collection reconnected her to the essential definition of “curator: one who is a steward or guardian, responsible for taking care of the objects. The shared goal of the team was to consider the physical space and to show the artworks in the best manner possible. Like the artworks on view in the Harper Center, the works that are part of Small Frequencies in McGiffert House carry the same spirit of art to be lived with and art to be experienced in ordinary, everyday settings.

Small Frequencies is now on view at McGiffert House*. All the works in the Harper Center of the Booth School are on permanent display. The Harper Center is open to the public during business hours from Monday to Friday.

*The McGiffert House is not open to the public. Those who are interested to see the exhibition may contact Canice Prendergast at Canice.Prendergast@chicagobooth.eduwith inquiries.

![display_CF_Tussle[2].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b6e16753917ee7c84915b51/1557846280936-D8TLAODTFHKNQVXEMQIF/display_CF_Tussle%5B2%5D.jpg)