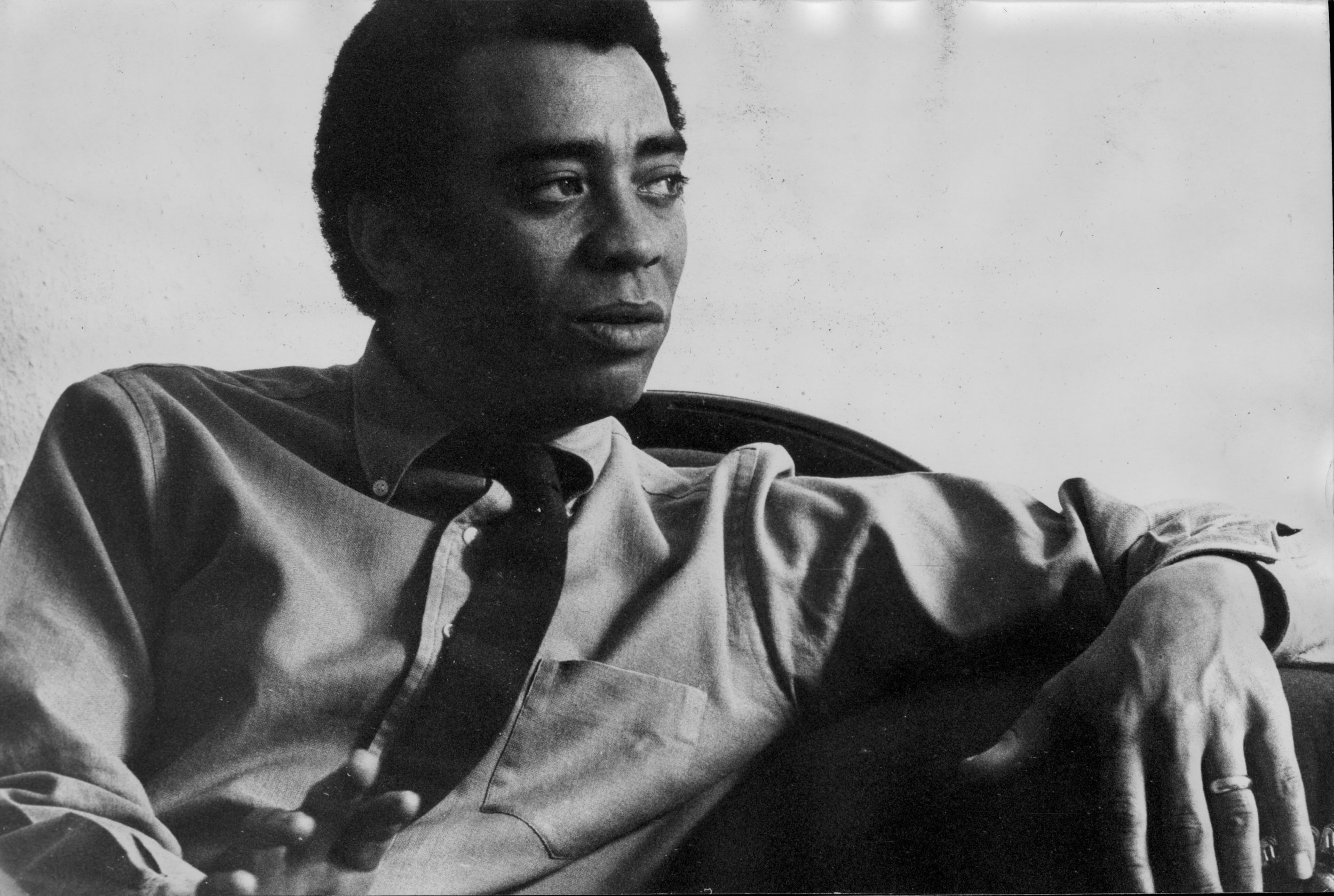

Our Dad was the Grand Pap of Rap: Oscar Brown, Jr.

Oscar Brown, Jr.

by Maggie and Africa Brown

On October 10, 2017—what would have been prolific Chicago-born entertainer and activist Oscar Brown, Jr.’s 91st birthday—Maggie Brown happened to meet Dan Logan at the Logan Center’s fifth anniversary celebration. It was there that Maggie, one of Oscar Brown, Jr.’s daughters, learned that the Logans (the benefactors of the Logan Center) were not only fans of her father’s work, but Dan even recalled interviewing him during his days as a journalist. This chance meeting led, just a year later, to the launch of the Oscar Brown, Jr. Archive Project at the Logan Center, with Maggie and her sister Africa—the two youngest of Brown, Jr.’s seven offspring—serving as co-directors and Artists-in-Residence.

The archive project’s purpose is threefold: to assemble, preserve, document, interpret, disseminate, and perform the various works created by Brown, Jr., a multi-talented singer, songwriter, composer, author, playwright, poet, essayist, and thinker; to expand access to his creative works by establishing an archival collection for research; and to produce some of his lesser known works and compositions for exposure to wider and younger audiences.

Born October 10, 1926, in Bronzeville, our father grew up absorbing the sights and sounds of his South Side community. He began performing early, as a teenager, and was one of the chief practitioners of delivering spoken word over jazz in the late 1950s. During the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, Brown became a pioneer in the entertainment industry, writing and performing songs, poems, and plays that celebrated African American life and the fight for social justice.

“There seemed to be a kind of poetic justice at work when Dan stepped forward to kick off our archival preservation efforts...it marked yet another example of the Logan family’s dedication to the arts.”

He combined various musical genres, such as jazz, blues, folk, and gospel, to fashion his message of justice, and enjoyed entertaining and educating his listeners, coining the word “edutainment” to describe his approach and style. “Edutainment”—the blueprint that he designed to transform despair into hope and promise by developing the natural talents of his people—is a marked contrast to the dehumanizing lyrics and violent imagery that have become far too prevalent today. Indeed, edutainment has been tragically underutilized in the face of endemic violence flowing from within and without disenfranchised black communities.

Our father went on to impact the jazz world, theater community, and Black Arts Movement, and was best known for his classic recordings “Sin and Soul” and “We Insist! Freedom Now Suite” with Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln. He was also a jazz lyricist (“All Blues,” “Afro-Blue,” and “Work Song”) and playwright, with musical productions rooted in the South Side of Chicago like “Opportunity, Please Knock,” produced with the Blackstone Rangers in 1967, to the pioneering “Kicks and Company” in 1961 at McCormick Place, and Off Broadway with Muhammed Ali starring in the title role in “Buck White.” But few people know that he authored over a thousand poems, wrote numerous essays, and brought the Jackson 5 and Avery Brooks to national attention through his Gary, Indiana Talent Show in 1968. Our father was committed to channeling his talents in an outpouring of prose, literature, and artistic expressions for what he called Human Improvement Potential (HIP), which he defined as any ideas or activities that advance the interests of humanity and involve making positive moves in healthy directions.

While greatly respected by literary contemporaries such as Lorraine Hansberry and Gwendolyn Brooks, our father may be one of the least-known Chicago writers of his era.

As mothers of three, we have seen first-hand what is being fed to young consumers of music and entertainment. We both share a sense of urgency to carry on the work started by our father; we believe that the dissemination and exhibition of his musical and literary works, along with sharing the Brown family story, is not only valuable to American history, but adds significantly to the catalog of positive artistic output that contributes to a healthy cultural environment. From the outset, the Logan Center made the most sense as a home for the archival project. As performers— Maggie, an acclaimed Chicago vocal performer; Africa, a singer, actress, and musician—we had already established a working relationship with Bill Michel, Executive Director of the Logan Center, and Emily Hooper Lansana, Director of Logan Center Community Arts, in the Logan Center’s opening days, and we appreciate the value of the facility for performance and exhibition in the community.

“The recognition and exposure of our father’s unparalleled body of work is past due, and as stewards of our family legacy, we are committed to making the archive a reality. Both of us are married to the music, and convinced that when the world can experience the unique style of artistic expression we grew up on, future generations will treasure it, too.”

Brown, Jr. said: "[With] the Grace of God we've got, [we] need never fire a shot." We believe that preserving, organizing, and making the works of Oscar Brown, Jr. available in a tangible way could unleash a healing cultural force—a force that requires harmonizing in a unified rhythm. In addition to conservation activities, we will highlight Brown, Jr.’s musical plays during our residency, several of which have been selected for staged readings. The first of five productions to take place at the Logan Center was on October 10: Journey Through Forever, which our father called a D.O.M.E.: dramatic organization of musical expression—a device that he developed as a way to organize and arrange various poems and compositions to effectively produce a full musical theatrical piece. The performance of Journey Through Forever set the stage for the residency with a packed house, and the date of the first reading was not lost on us: It took place a year to the date of Maggie’s meeting with Dan Logan, and would have been our father’s 92nd birthday.

The Oscar Brown, Jr. Archive Project will be a treasure trove of poetry, literature, music, and stage plays created by this Chicago artist and deep -thinker whose work was sometimes suppressed and conveniently labeled as ahead of his time.