“It’s About Wonder” - Ten Years at ASCI

Arts, Science + Culture: Celebrating 10 Years

By Ellen Wiese

Julie Marie Lemon has always been interested in revealing what cannot be seen at first glance. While working on her Master’s thesis at The University of Chicago, she examined how images from the Hubble Space Telescope mirror the conventions of oil paintings from the Baroque period. In both the Hubble composites and the paintings, Lemon found, tiny details were made visible. “Deep down,” she says, “There are these connections.”

These connections—invisible, powerful, and potentially field-altering—formed the basis for Lemon’s brainchild: the Arts, Science + Culture Initiative (ASCI).

The curricular programs and arts organizations at UChicago focus on innovation—a drive to discover the next great scientific breakthrough, shape the future of literary criticism, or craft a renowned work of art. The University defines itself by its discourse, rigor, and commitment to producing the best possible results through critical debate.

But the culture of lively disagreement that the University is famous for is only half of the equation. The other component is collaboration, both within fields of study and across disciplines. ASCI, which recently celebrated the 10-year anniversary of its founding, has championed open-minded, multi-dimensional, transdisciplinary understandings of the world and supported the collaborative creation of some of the highest-quality art, science, and social science at UChicago as a result.

“Working with [Lemon] and ASCI over the past decade has produced some of the most memorable & dynamic collaborative programs in my time at UChicago.”

—Zachary Cahill, Director of Programs & Fellowships at the Gray Center

Strong Foundations

In 2001, a report authored by faculty, students, and staff established the groundwork for a multidisciplinary arts center—later to become the Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts—and the suite of innovative programs the building would house. Ten years later, while this new hub of arts activity on campus prepared to offer an array of programs, little formalized connection existed between the arts and STEM disciplines. Lemon found herself motivated by a series of constitutive questions: What can we learn by bringing the disparate fields of the arts, sciences, and culture into dialogue? Will examining the spaces between disciplines yield new ways of thinking? How does the exchange of methodologies, tools, specific questions, and curiosities advance our thinking?

The challenge lay in devising answers to these questions at the University of Chicago in particular. At the time, the University offered no sciences that were evidently cross-disciplinary in the way that fields like engineering, architecture, or design might be. And Lemon resisted familiar, cursory answers—for example, a painter illustrating a biology textbook. So, in 2010, she founded the Arts, Science + Culture Initiative on the principle of bringing together graduate students and faculty from across disciplines and observing the results of their collaborations. Lemon’s initial role was to find the people whose work and philosophy would speak to one another—to play matchmaker for connections that could spark something profound.

Julie Marie Lemon, center, poses with Josiah P. Zayner (left), PhD’13, and Francisco Castillo Trigueros, PhD’13, during their collaborative Chromochord project. (ASCI, 2012-13). Photo: Robert Kozloff

ASCI was charting a new path for trans-disciplinary thought at the University, soon to be joined by programs like the Gray Center for Arts and Inquiry and the Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society. From the beginning, Lemon says, graduate students were some of the most enthusiastic participants—they were open to new ideas and settled easily into unfamiliar forms and fields of work. Their enthusiasm resulted in the initiative’s longest-running and perhaps best-known program: the Graduate Collaboration Grants. Awarded yearly since 2010, these grants fund teams of at least two graduate students of different fields for a year of sustained work on a collaborative project. With the grant’s financial support, participants weave together the unique perspectives offered by their disciplines into a culminating project, aided by staff support, monthly forums, and exhibition, publication, and presentation opportunities. Alongside the establishment of the Graduate Collaboration Grants, faculty feedback resulted in a number of programs, symposia, and collaborations in which ASCI acted as a forum, amplifier, and creative partner in the cross-disciplinary work of faculty participants.

From these foundations, the program embarked on a period of thoughtful, flexible growth. The initiative, rooted in ideas of experimentation, innovation, and evolution, held close to these values as it developed. “[Lemon] was smart enough to think, okay, we’re starting here,” says Matthew Jesse Jackson, Professor in Art History, Chair of the Department of Visual Arts, and ASCI Faculty Leader, “But then she saw what came in, and she modulated the program to what would work. The program changed to respond to the producers, rather than making the producers respond to the program. It showed such a degree of respect for early-career makers and thinkers.” The Neubauer Collegium and the Gray Center came online in 2012 and 2013 respectively, and faculty would often bring ideas to ASCI to incubate before seeking continued funding from these institutions.

“Working with [Lemon] and ASCI over the past decade has produced some of the most memorable and dynamic collaborative programs in my time at UChicago,” says Zachary Cahill, Director of Programs and Fellowships at the Gray Center. “Whether for partner programs that probed the ethics of Nuclear Science and artistic responsibility during the commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the Chicago Pile-1; elaborated the differences and areas of overlap in the sciences and the humanities as it relates to what constitutes an experiment; or thought through the scientific facts of time travel in the context of Afrofuturist Art, Literature, and Music, the Gray Center has been enriched by Lemon's expertise in bridging the (mis)perceived divide between artistic practice and science—thus helping us to have a clearer picture of our world."

In the first few years, a number of graduate students expressed a desire to engage more broadly without collaborating on specific projects. To that end, ASCI established the Graduate Fellows program in 2014 for students whose work is firmly anchored in the arts, humanities, social sciences, or sciences, but for whom crossing disciplinary boundaries—between physics and music composition, anthropology and visual arts, or art history and evolutionary biology, for example—is integral to their practice and research. The program emphasizes points of connection between these fields; accordingly, Graduate Fellows meet monthly for discussion of their projects, tools, and methodologies. A year after the Graduate Fellows program was established, the Graduate Collaboration Grants expanded to enable inter-institutional collaboration with MFA candidates at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). Also in 2015, ASCI launched Field Trip / Field Notes / Field Guide, a three-year pilot program designed to develop an interdisciplinary community engaged with Chicago’s vibrant urban environment. A consortium of Fellows from UChicago, the University of Illinois at Chicago, SAIC, and Northwestern University built a series of expeditions, readings, meals, and discussions utilizing the city as a unique platform for exchange and connection across disciplinary and institutional boundaries. After an academic year of research and urban exploration, each cohort produced a Field Guide highlighting and examining their distinctive approaches to research and practice while “in the field” (all three Guides are available here).

In fall of 2016, Naomi Blumberg joined the staff of ASCI as Program Coordinator and later Assistant Director. Her background includes positions at the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum and the Chicago History Museum, but what drew her to this role, she says, was the opportunity to mentor graduate and undergraduate students. “We get extraordinary students with really good ideas—often very big ideas—and the results have been so impressive and exciting to watch,” says Blumberg. “I love helping them along the process. I learn so much from the students every year.”

Success, Tangible and Intangible

The Phoenix Index (2014–15)

Graduate student projects began to experience remarkable success—in the arts and beyond. “There have been projects I’ve seen,” says Jackson, “that I thought to myself, ‘Wow, that is one of the best things I’ve seen on campus, period.’”

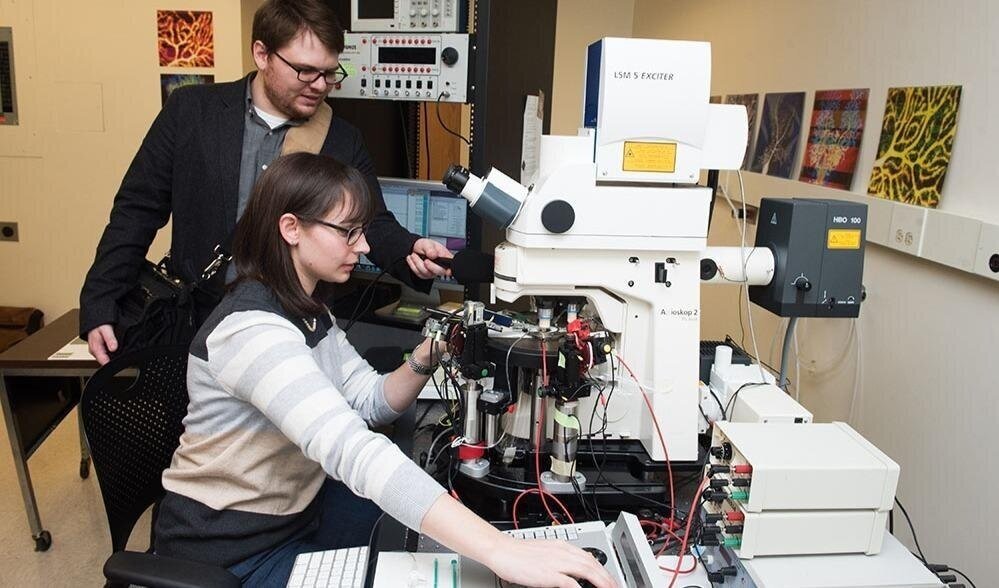

In 2014, Shane DuBay, PhD candidate in Evolutionary Biology, and Carl Fuldner, PhD candidate in Art History, collaborated on a project that would eventually become The Phoenix Index: A New Method in Environmental History. In a survey of the extensive collections of bird species at the Field Museum, the pair noticed that birds collected over certain time periods had noticeably darker plumage. By photographing complete sets of select species, they devised a novel means of tracking industrial pollution based on the relative amount of soot covering each bird; this method provided data dating back decades before coordinated systems for measuring air quality were put in place. The photographic time-series in The Phoenix Index are a work of art, a reflection on pollution and the effects of humanity on our environment—and an entirely new, scientifically valuable method for assessing the rate of planetary change. The team’s findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and covered by outlets including the BBC and the New York Times.

Dr. John Bates, Curator of Birds at the Field Museum and a member of the Committee on Evolutionary Biology at the University of Chicago, was first introduced to ASCI as Shane DuBay’s faculty advisor for The Phoenix Index. Initially, he had no expectations for the project’s scientific impact. “Communicating the science to people who are not scientists is an amazing opportunity,” Bates says, “And then being able to actually learn something about the science is an unexpected and amazing boon.” That said, he adds, “It’s not about getting science done or getting art done: it’s about the synergy between the two. You don’t know what’s going to happen until you put those two in conversation.”

Power Structures: Connotations of the Facade in State Architecture (2017–18)

ASCI collaborations have been equally fruitful between the arts and social sciences. In 2017, Elizabeth Jordie Davies, PhD candidate in Political Science, and Ayesha Singh, MFA student at SAIC, collaborated on Power Structures: Connotations of the Facade in State Architecture. They returned to their hometowns and took photographs and rubbings of monumental government structures: a Confederate monument outside a U.S. courthouse and the Rashtrapati Bhavan, a building used by the British during their occupation of India. By producing large-scale recreations and photographs of these monuments, they considered the entrenched divisions of power in American and Indian society and the structural legacies of racism and colonialism. “This is pushing us towards these spaces where there are conversations that could be very fruitful to our own societies,” Singh said in 2018. In light of the protests against anti-Black state violence over the past year, this work has attracted renewed attention. In a recent article in In Practice, Davies and Singh consider how recent protests in both the U.S. and India have rejected monuments to Confederate and colonial pasts and taken up new monuments as a challenge to state power.

Even those who were initially skeptical of ASCI have come around, seeing the success of the program. Many early doubters have become enthusiastic collaborators, including Jackson. “I went through a stage of transformation,” he says. “For me, it’s been eye-opening.”

“I really think that beauty, joy, & curiosity should be good enough reasons to pursue what you want to pursue.”

—Tanvi Gandhi, PhD candidate in Physics

Setna (2020-21)

Dripping, Creaking, Flowing: Narratives of Hydrological Change in Antarctica (2018–19)

Invisible/Invincible: The Bacteria Survival Guide (2017–18)

Randomness and Mindgames (2016–17)

Molecular Movement (2015–16)

ASCI in 2021

These days, ASCI takes a three-pronged approach to its mission of building an “ecology of perspectives.” Its graduate student programs continue to provide support and engagement for students from more than 25 disciplines. Between 2010 and 2019, ASCI awarded a total of 86 grants to cohorts and individuals. The Collaboration Grants program has awarded a total of $258,000 in support of 49 collaborative projects among 118 individuals, while the Graduate Fellows Grant program has awarded $90,000 in support of 37 individual grants to six cohorts of Fellows.

ASCI has highlighted the work and accomplishments of these graduate students through a series of video interviews. “I’m always so thrilled and in awe of how these grad students put so much into their projects, and follow through, and continue to move on after the program,” says Lemon. While the initiative is co-curricular, it is not degree-granting: graduate students pursue their projects out of intense independent interest.

Beatrice Fazio, PhD candidate in Italian Studies, and Tanvi Gandhi, PhD candidate in Physics, make up one of four teams that received a Graduate Collaboration Grant for the 2020-2021 term. Their project, Dante in the Lab, explores the interplay of contemporary physics and medieval literature by recreating the literary imagery of the Divine Comedy in the laboratory. For both, this partnership has led to unexpected insights—and emphasized the importance of collaborations between arts and sciences in general. “I really think that beauty, joy, and curiosity should be good enough reasons to pursue what you want to pursue,” says Gandhi, “But there’s a more serious issue, from a practical point of view, where people are losing their trust in science.”

“This is my favorite program in the University. . .it’s not only about education, it’s about wonder as well.”

—Dr. Douglas R. MacAyeal, Professor, Geophysical Sciences

In addition to expanding the audience for science and building back that trust, scientists benefit from working with experts in other fields as well. Gandhi knows of a robotics research group whose team includes a consulting origami artist. “They carry a lot of knowledge in their experience,” she says. “It’s really practically useful. And so we’re seeing a lot of really beautiful collaborations come out of allowing people to bring their expertise together, rather than trying to invent the wheel from scratch.” Finding a shared vocabulary has required both Gandhi and Fazio to slow down and examine aspects of their work through a fresh lens. “It brings such a huge difference in the way you think,” Fazio says. “When I talk to Tanvi, for example, I find that the way I speak to her and explain things to her as a physicist—it’s not simplifying my work, but it gets me to explain my work in a more clear way, in a way that one day I will express things to my students.”

Dr. Douglas R. MacAyeal, a professor in the Geophysical Sciences whose focuses include glaciology, cryospheric science, and ice and climate, has been the faculty advisor for several graduate projects funded by ASCI, including Scaling Quelccaya (2015-2016) and Dripping, Creaking, Flowing: Narratives of Hydrological Change in Antarctica (2018-2019). “I absolutely love this part of the University,” MacAyeal says, “It’s the most vibrant collaboration I’ve ever had with any other part of the University, aside from being in the trench, teaching.” The central value of the program, MacAyeal says, lies in nudging both the scientists and artists out of their “low energy states.” For him, it resulted in a renewal of his perspective as a scientist. “This is my favorite program in the University, except for yours truly’s program,” MacAyeal added with a laugh.

ASCI has also grown into an academic incubator for UChicago’s faculty, supporting and assisting in the development and organization of projects across the disciplines through collaborations with more than 40 faculty members. Faculty projects include multidisciplinary classes such as “Images and Science,” co-taught in 2014 by Professor W.J.T. Mitchell and Norman MacLeod, and “Exploring the Body in Medicine and the Performing Arts,” co-taught in 2016 by Assistant Professor of Medicine Brian Callender, MD, and Associate Professor in the Department of Visual Arts (DoVA) Catherine Sullivan. The former led to Mitchell’s 2015 book Image Science: Iconology, Visual Culture, and Media Aesthetics, while the latter was recently offered for a second time through the Stevanovich Institute on the Formation of Knowledge. Sullivan’s class was developed as a result of an earlier proposal with longtime collaborator, dramaturg, and performer Assaf Hochman on somatic practices and pedagogies that use the body as an instrument for research. After developing a video archive called the Corporatoreum, they devised a series of short musical compositions based on movement pedagogies from the Alexander Technique to butoh. “This work would not be possible without ASCI,” says Sullivan. “There wasn’t anything like the Corporatoreum on campus—pedagogy that conflates somatic practice with the histories and methods of the pedagogies we studied.”

In 2017, ASCI hosted a residency with Berlin-based artist Tomás Saraceno, who worked with astrophysicists, cosmologists, and soft matter physicists to visualize cosmological systems and cosmic dust. A conversation between Saraceno and MoMA associate curator Yasmil Raymond, co-presented with the Goethe Institut, was included in the Chicago Architecture Biennial, and his work with scientists at the University culminated in the video artwork The Politics of Solar Rhythms: Cosmic Levitation, which was part of the 2018 exhibition Carte Blanche to Tomás Saraceno: On Air at the Palais De Tokyo in Paris. In addition to specific collaborations, ASCI has worked closely with faculty on several conferences and symposia, including Communicating Science (2014); Fabricating Color: A Multidisciplinary Conference on Color and Method (2014); and Discovering New Truths: Exploring the Concept of Experiment Across the Disciplines (2018).

Finally, ASCI conducts a variety of public programming—from video installations and exhibitions to roundtables and artist talkbacks—with the goal of engaging with and disseminating information to the UChicago community, the city of Chicago, and beyond. These public programs have focused on topics as wide-ranging as digital culture, sci-futurism, experimental imaging, and cabinets of curiosity. In 2017, ASCI commissioned a sculpture by artist and alumnus Dan Peterman in conjunction with the second Chicago Architecture Biennial called Slipping and Jamming: Variable Installation of Z-Forms. Working with the physics lab of Sewell Avery Distinguished Service Professor Heinrich Jaeger, Peterman utilized granular material research to build a large sculpture in the Eckhardt Center composed of thousands of post-consumer reprocessed plastic elements, each cut into the shape of a Z. The column is secured in its stable shape not by orderly arrangement of the pieces, but by random, disordered configurations that are more akin to a liquid than a solid. In Peterman’s sculpture, these concepts of physics, usually studied at a micro level, take on a human scale, pointing not only to the scientific ideas at play but also the stability and flow of invention, production, and generation (check out the public talk with Peterman and Jaeger as well as the sculpture’s installation and deinstallation).

Temporary installation of Slipping and Jamming in the atrium in the atrium of UChicago’s William Eckhardt Research Center.

ASCI’s unique focus on collaboration between the arts, physical and biological sciences, and social sciences is just part of the program’s extraordinary success. The rest is built on the attributes the program draws from all three areas—and the ways it resists classification into any. “It functionally occupies this undefined anarchic space,” says Jackson. “That’s been an amazing strength for the program, because it meant that nothing was out of bounds.” ASCI refuses to be lumped into any restrictive category while maintaining a commitment to improvement—in its evolution since 2010, it has redoubled its support of the things that worked, set aside the things that didn’t, and continued to reinvent what it could be. “This is a free space,” Lemon says. This ethos results in a rejection of simple ideas or predetermined outcomes: the program and those involved share methodologies, approaches, and ideas from widely ranging fields, creating a relationship in which each party is both apprentice and expert. SAIC MFA candidate Meredith Leich, who worked with glaciologist Andrew Malone in 2015-2016 to create a 3-D map of the retreating Quelccaya Ice Cap overlaid on the city of Chicago, highlighted the complexity of thought her project was able to engender. “It illuminated what’s actually happening in a world that’s changing in a way that allows for a greater diversity of reactions than just ‘I’m scared’ or ‘the world is ending,’” she says (the full-length film that Leich created as a result of the collaboration won the video art competition MACHT KUNST; Malone presented their work at the American Geophysical Union in 2017).

ASCI cultivates an intentionally welcoming, friendly atmosphere. “You go there to feel that you’re going to be in a safe space—with no negative connotations attached to ‘safe space,’” says Jackson. “It’s a place where you can try stuff and talk to people.” It is precisely this collaborative, process-centric approach that has led to the program’s success. Many of the students who started their collaborations with funding from ASCI have continued their partnerships after the program, and work that began in Graduate Collaboration Grants or Fellowships has expanded into the world in impressive ways. Often, says Blumberg, participants “find this really important bond that turns into friendship, but also turns into long-term collaboration. People continue to work together, and we hear back from them a few years later. It’s really exciting to see that it comes from this small, chance moment where they meet and they say, ‘This is an idea we can work on together.’” Shane DuBay, the evolutionary biologist behind The Phoenix Index, has continued his work on charting pollution through soot accumulation on bird feathers; he is now an Assistant Professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Michigan. Meanwhile, his partner in the project, art historian Carl Fuldner, went on to work in the Photography Department of the Art Institute of Chicago. An independent evaluation by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) in 2019-2020 found that 92% of participants said that the program had influenced their professional work in the long term.

Ultimately, ASCI succeeds because it doesn’t lose track of the curiosity and surprise of discovery and creation. This is partially due to a concept it adopted from the sciences: welcoming productive failure in the process of playful experimentation. “One of the things that is certainly true in art, but I’m guessing any scientists will tell you as well—not a lot of major breakthroughs come from people being angry,” says Jackson. “The fact that there’s a little bit of pleasure in it is underestimated as a tool for insight and knowledge. The program is very much knowledge-bearing, it’s very much related to research, but it doesn’t necessarily feel or look that way.” MacAyeal agrees: “It’s not only about education,” he says, “It’s about wonder as well.”

“This is a free space. . . the program and those involved share methodologies, approaches, and ideas from widely ranging fields, creating a relationship in which each party is both apprentice and expert.”

—Julie Marie Lemon, Director & Curator, ASCI

What Comes Next?

In addition to continuing to support and engage with the extraordinary work of its graduate students, faculty, and public programs, ASCI is looking to expand its programming into new areas. Lemon and Blumberg are developing a version of the Graduate Collaboration Grants aimed at undergraduates; instead of collaborating for a year, student participants from different fields will be paired up for a quarter-long collaboration. While the ongoing uncertainty of COVID-19 makes long-term planning difficult, the pilot program is scheduled to commence potentially as early as 2021-2022.

In 2018, ASCI launched The WATER Project: Research and Cultural Production to address critical international issues related to climate change. The program is designed to provide a platform for discourse around local and global issues related to water and includes faculty and scholars in the Humanities, Social Sciences, and Biological Sciences; 26 scientists at Argonne National Laboratory; and artists working with water as a social issue and material. The ongoing project offers dynamic and far-reaching infrastructure for water- and climate-related programs on campus, including roundtables, performances, exhibitions, commissioned artworks, research efforts, public programs, and course offerings. As the WATER Project expands, Blumberg is excited at the prospect of more long-term projects on that scale. “Every year is a new beginning of great ideas and new relationships,” she says.

The WATER Project is now in its third year, while the undergraduate pilot program will launch in the next few years. These initiatives will join the remarkable and ongoing work undertaken by faculty and grad students and continue to facilitate insight, research, and conversation at the overlap between disciplines. ASCI has ambitious plans for the future; at the same time, part of the beauty of the program is that it’s impossible to predict exactly what innovations will result from these collaborations. “You can’t even begin to overestimate the potential for those kinds of collaborations,” says Bates. At this point, more than 10 years since the program’s founding, “it’s had time to distill exactly what it wants to be,” says Jackson. “It’s a natural time for growth.”