Repotting Constructions of Beauty With Passionate Signals

A new exhibition of artist Martha Rosler’s work at the Neubauer Collegium reveals pretty pictures of flowers are anything but innocent

by Jad Dahshan, third-year student studying Art History and Chemistry

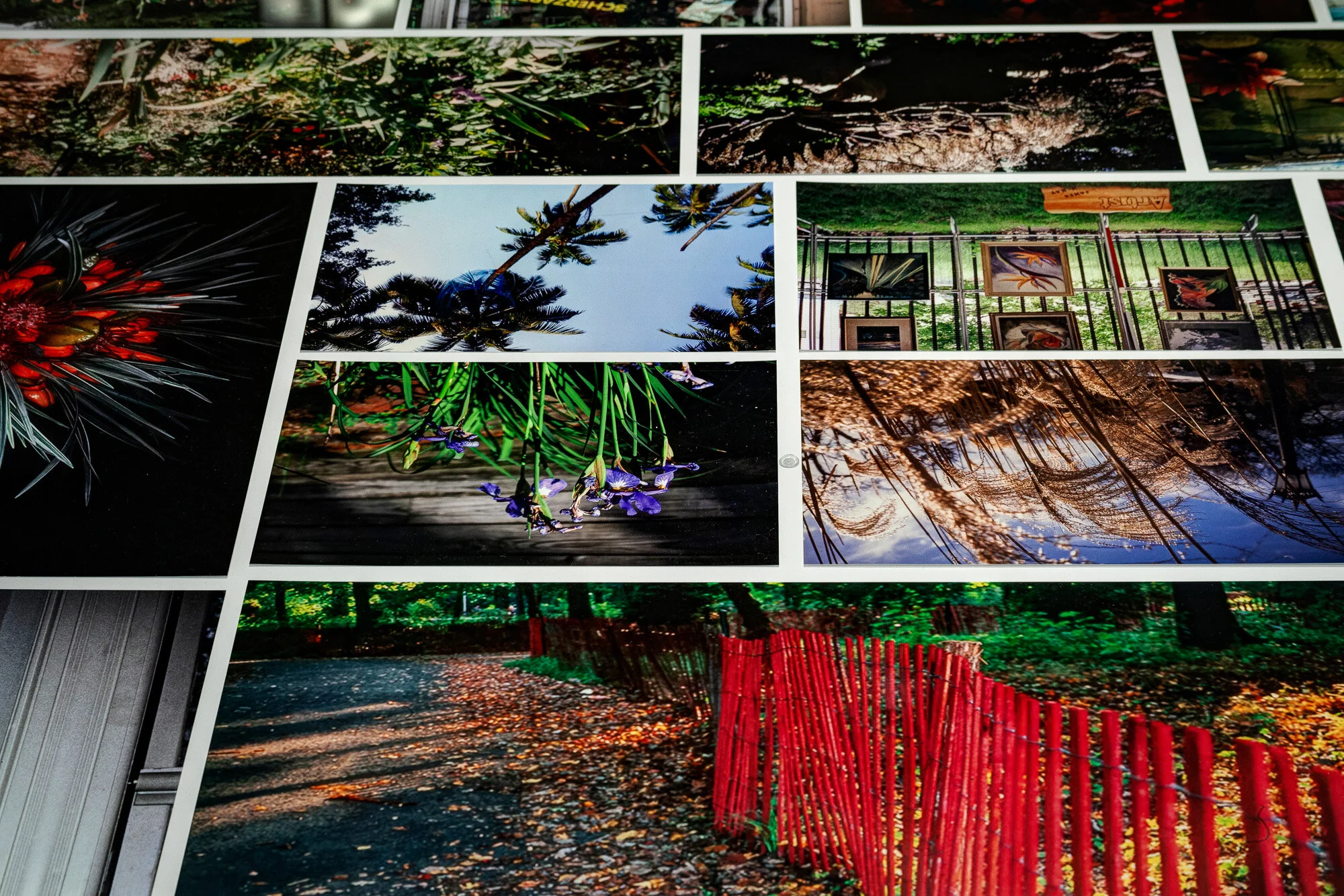

Installation view: Martha Rosler: Passionate Signals, Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, University of Chicago, September 17, 2019 - January 31, 2020. Photo: Robert Heishman.

At an early 1600s production of Hamlet at the Globe Theatre in London, a grief-torn Ophelia handed out flowers to those around her: rosemaries “for remembrance,” and pansies “for thoughts.” Fast-forward a century, to the Dutch Golden Age, and prolific still-life painter Rachel Ruysch has added the final touches to a painting brimming with botanical and vegetal symbols. Hundreds of years later, an adman and florist coin the slogan “Say It With Flowers,” inaugurating floriography into an age of consumerism.

These vignettes illustrate how the history and language of flowers is intertwined with ideas of beauty, labor, and power, all themes explored in a new exhibition at the Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society. Martha Rosler: Passionate Signals, curated by Dieter Roelstraete and on view through January 31, 2020, features photography, video, and installation work by the Brooklyn-based artist depicting plant-life. The exhibition falls into a centuries-old timeline of depicting of flowers in art, often for the sake of beauty or to signal wealth, as a tulip would have done in a Dutch still-life. More broadly, these images utilize a system of symbols in which different species are assigned unique meanings, as is the case with Victorian floriography or even modern-day floral businesses. However, Rosler is not concerned with developing a new floral orthography; she is not recycling the same signifiers into the 21st century or suggesting new meanings. Instead, Passionate Signals uproots the language of flowers and the business of beauty to expose the systems that give soil to it—those that are often patriarchal, capitalistic, and nationalistic.

Installation view: Martha Rosler: Passionate Signals, Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, University of Chicago, September 17, 2019 - January 31, 2020. Photo: Robert Heishman.

Installation view: Martha Rosler: Passionate Signals, Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, University of Chicago, September 17, 2019 - January 31, 2020. Photo: Robert Heishman.

Since the late 1960s, Rosler has been producing work in mediums such as photography, video, collage, painting, performance, conceptual art, and installation. Through both art and writing, she problematizes divisions between the public sphere and personal worlds, and tackles issues of war, domesticity, gender inequality, gentrification, and wealth distribution, among others.

Roelstraete first became acquainted with Rosler in 2006 while organizing Academy, a show in Antwerp, Belgium which dealt with the idea of the pedagogical environment as an art space. e-flux, a publishing, archival, and curatorial platform had just launched Martha Rosler Library, a travelling reading room comprising thousands of books taken from the artist’s overflowing library. Considering that Rosler was a professor at Rutgers University at the time, Roelstraete and his colleagues found it highly appropriate to incorporate the library into the show.

A year later, at Documenta 12, the exhibition of contemporary art that takes place in Kassel, Germany every five years, Roelstraete first saw some of the photographs that would feature prominently inPassionate Signals. He began to acquaint himself with Rosler’s passion for gardening, the freshly cut bouquets in her home, and the many pictures she’s taken of plant-life all over the world.

Installation view: Martha Rosler: Passionate Signals, Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, University of Chicago, September 17, 2019 - January 31, 2020. Photo: Robert Heishman.

More than 60 photographs make up a central piece of the exhibition, displayed on a table in the center of the Neubauer’s gallery. The table is surrounded by historical video pieces, hanging embroidery works, and an installation.

The installation, titledB-52 in Baby’s Tears dates to around the time Rosler made her seminal House Beautiful: Bringing the War Homephoto collages, which are housed in the Art Institute of Chicago’s collection. (The House Beautiful series was originally made as anti-war flyers, interposing images of human suffering, violence, and destruction from the Vietnam War into magazine pictures of luxurious home interiors targeted at middle- to upper-class, white, heterosexual consumers.)

Installation view: Martha Rosler: Passionate Signals, Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, University of Chicago, September 17, 2019 - January 31, 2020. Photo: Robert Heishman.

B-52 in Baby’s Tears is what Roelstraete refers to “as a domestically-scaled earthwork.” The work is a modestly-sized rectangular box containing a bed of Soleirolia soleirolii, a common houseplant and type of nettle colloquially dubbed “baby’s tears.” The dark silhouette of a B-52 bomber plane interrupts the delicate plant’s growth, a model which had been deployed in the Vietnam War to raze villages and, as the title of the artwork makes clear, took the lives of many, including children. The work recalls the land art of the 60s and 70s, a movement which sought to create large-scale, outdoor installations using natural materials like boulders and stones. “When you think of land art and environmental art, you think about people like Robert Smithson and their giant machines and Spiral Jetty in Salt Lake in Utah,” says Roelstraete. “Then Martha’s response or her retort to this very macho, heroic enterprise is this very small but poignant [work].” The piece could very well be grown inside someone’s house.

Indeed, the home figures greatly in Rosler’s body of work, from one of her most-recognized video pieces, Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975), and even her UC San Diego MFA thesis project, A Gourmet Experience.

But in Passionate Signals, Rosler turns from the living room and the kitchen towards the garden as a site at the interstice between male leisure and frequently forgotten feminine labor. What makes the exhibition unique is that it is the first to solely examine this green, horticultural slice of Rosler’s explicitly political body of work. In doing so, it gathers works made as recently as June 2019 and dating as far back as the 1970s.

“What I wanted to do with Passionate Signals was focus on a lesser-known aspect of Rosler’s work,” says Roelstraete, noting he wanted to concentrate on pieces that had more ambiguity. “The idea of a flower is just so alluring. There’s this site of ambivalence in a way; it has the innocence of a very private aesthetic experience, but what are the politics of that? What are the economic conditions of producing it?”

Installation view: Martha Rosler: Passionate Signals, Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, University of Chicago, September 17, 2019 - January 31, 2020. Photo: Robert Heishman.

Passionate Signals does not attempt to offer viewers the answers to these questions on a silver platter. In the catalogue for Rosler’s recent retrospective at the Jewish Museum, Rosler speaks to the “as if” aspect of her work—“a suggestion of work” or “a sketch, a line of thinking, a possibility”—in an interview with Benjamin Buchloh, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art at Harvard University. In Elena Volpato’s essay in the same publication, the writer elaborates upon Rosler’s intentions “to arouse a need to continue the research she has initiated.” As such, the works on display in Passionate Signalseffectively prime the viewer to anticipate, seek out, and question the systems of labor and power underlying the production of beauty, specifically that of flowers. A work that vividly demonstrates this is the 1974 Super 8 film, Flower Fields.

Flower Fields is an allusion to color field painting, an offshoot of Abstract Expressionism that prioritized color and emotion, forsaking form and socio-historical context. Color field painting sought transcendence and aesthetic mysticism in large swaths of color, of which the flower fields at the beginning of Rosler’s video are reminiscent. In Rosler’s words, the work depicts mostly undocumented workers along the West Coast’s Highway 5. When the camera closes in on the color-striped hillside, laborers can be seen, and later, immigration police at their mobile roadblock. Roelstraete explains that this is typical of Rosler, to subvert the escapism of her color/flower fields via the zoom-in motion so that the laborers slowly gain visibility and recognition. “The amazing thing about this work is how relevant it now all of a sudden becomes, with this ongoing panic around immigration,” he explains.

Installation view: Martha Rosler: Passionate Signals, Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, University of Chicago, September 17, 2019 - January 31, 2020. Photo: Robert Heishman.

Installation view: Martha Rosler: Passionate Signals, Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, University of Chicago, September 17, 2019 - January 31, 2020. Photo: Robert Heishman.

“It’s a kind of picking at something that makes you uncomfortable, and through that discomfort, asks that you think about what you’re looking at in a different way,” says Laura Letinksy, photo artist and professor in the Department of Visual Arts. Although Letinsky comes from a different photo-making tradition, her and Rosler’s work intersect in several ways. Both make work about what she says is the “labor of the home as an ideology and as a practice.”

“To make a home, there’s a huge amount of cultural production around it, as well as labor that is often women’s work,” Letinsky says.“The underlying conceptual instrumentality of the work is to try to get people to think about what home means, because home is often taken as something that’s very natural and innate, and actually, it’s very highly produced, and there’s a lot of work that goes into it.”

Backyard Economy II (Diane Germain Mowing), another Super 8 Film in Passionate Signals, acknowledges that labor. Rosler films a woman strenuously mowing her lawn, going back and forth across it, with laundry drying in the wind. It looks at the home as “a mechanism for the domestication of women,” as art historian Mark Wigley put it, and in doing so invites awareness as well as rejection. The work is neither specifically about the eponymous character, nor about the garden or even beauty, but about the unseen or ignored systems of labor, power, and control that are inherent to them. Watching the video therefore radically alters the experience of perusing the photos on view in the exhibition: No longer are the pictures of private gardens, public parks, and floral arrangements images of edenic, natural beauty. Instead, they are charts that map out the invisible hands that mow lawns, tend to flower beds, and arrange bouquets.

Installation view: Martha Rosler: Passionate Signals, Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, University of Chicago, September 17, 2019 - January 31, 2020. Photo: Robert Heishman.

While the exhibition does not itself illuminate the politics of, say, the United States’ flower industry, it examines routines of domesticity and beauty within everyday life, an apt analogy to contemporary systems of power and labor.

“If anything, [Rosler] is more relevant than she’s ever been, but that has to do with the fact that these are really dark and desperate times that call for angry art and for indignation, ” Roelstraete elucidates. “You know, she’s an angry artist, she’s someone who is forever repelled by the way the world is, as we all should be, and I share her feeling entirely…but maybe that’s why flowers, in a way, right?”