Stillness Complicated by Corners: A Reflection on Anne Carson’s Lecture Series

By Reema Saleh

In a series of lectures—“Stillness,” “Corners,” and “Chairs”—Anne Carson spent the better part of a week at the University of Chicago. Passing time between reading period and impending finals, I found myself sitting starry-eyed at “Stillness” and “Chairs” as well as a writing workshop hosted by Critical Inquiry, where we admittedly didn’t do much writing at all. Each time I wasn’t sure what to expect, and each time Carson left the stage, I wasn’t immediately sure what to make of it.

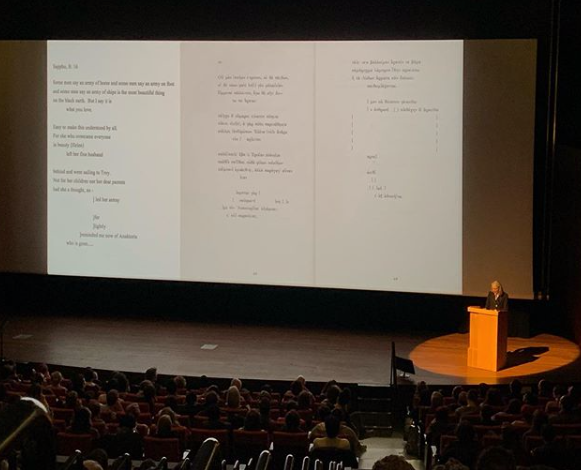

Anne Carson’s lecture “Stillness” at the Logan Center for the Arts. Photo by Critical Inquiry.

Stitching together a history of stillness from John Cage’s “4’33” to Emily Dickinson, Virginia Woolf, and Helen of Troy, she placed ancient and modern hand in hand. She traced fragments of Sappho with absent text to Antigone’s resignation to her fate as someone in between life and death. She traced those in turn to the murkiness of Jenny Holzer’s Dust Paintings, a series composed from censored texts detailing the conditions leading to the death of an Afghan prisoner in U.S. custody obtained via Freedom of Information Act requests.

In “Chairs,” Carson was accompanied by dancer and choreographer Jonah Bokaer. Over the evening, she traced the history of the chair from the electric chair to the 1964 “Electric Chair” series by Andy Warhol consisting of enlarged photographs screen printed with silver acrylic paint and later reprinted in bold, popping colors, exploring his theory that “when you see a gruesome picture over and over again, it doesn’t really have an effect.” She spent time musing over the importance of the chair—as a place of rest and work, a center of attention and power, a cultural norm we accept because of its presence in our lives.

“Seated Figure With Red Angle” by Betty Goodwin, 1988. Photo by ArtForum International.

Jumping back centuries, she brought us to Homer, to Odysseus’s final disguised conversation with Penelope, where “she mostly tells the truth and he mostly lies” and his seemingly endless journey finally reaches an end, or even a pause, when a woman asks him to sit down. All the while, Bokaer continues dancing on stage, with and around a chair—a performance that became distracting as I switched back and forth between watching his movements and watching Carson at the podium. Chairs became the natural conclusion to her lecture series because, as she puts it, they are “stillness complicated by corners”—something she made transparent as soon as she began speaking, but something I still had to unravel until it stuck. Finally, we arrived at a poem crafted entirely out of if-clauses, one she composed in response to a painting by Betty Goodwin titled “Seated Figure With Red Angle,” inspired by the awkward resting position of the figure, what they must be feeling, and if they’d “forgotten to exhale, as people with dementia often do.” As she ran through the last lines of her poem, she walked over to Bokaer, who finally sat on his chair on stage, and rested her hands on his head, ending the lecture without answering any questions. Walking from Mandel Hall into the night left me with the intense feeling that I had learned plenty during the series, but I could not put my finger on what exactly—something I quickly realized when trying to rehash the lecture for a friend. Still, I can’t say I was disappointed. Carson is a poet and classicist I understand at a great distance, from reading Autobiography of Red and “The Glass Essay” and listening to her speak all week. Lost, but not confused. Transparent, but still itching to understand. I was left with more to engage with during the brief interlude between reading period and finals—a glimpse of the understanding that I’d have to get to on my own.

In a workshop hosted by Critical Inquiry, Carson and her husband Robert Currie began the session by telling us there are two things we’re not supposed to do as writers: collaborate or do anything but write. Perhaps to spite this, they had us do both. I had my writing notebook in hand, and I was bewildered to find that instead we were setting out to find a boundary and reconstruct it with a partner. I’m sure we all felt quite silly—some of us creating physical barriers from debris, some examining the separation between childhood and adulthood, some talking through physical barriers and differences. Carson finds the discongruities in ancient and modern language and discovers a way to paint them anew—the way we all felt watching Bokaer dance across the stage in time with her last poem.

Admittedly, I did start to write something at the workshop. But only something fragmented, towards the end of the workshop. My poem, (If) Still Water Hangs Free, is mostly about growing up and being confused, and it is below.

(If) Still Water Hangs Free

Morning light rips pink through the sky.

A trickle of water downs my forehead.

Orange sprays the bright.

A wave slides under, half-sand half-water.

I came to the gulf as it emerged

sat in this chair, looked over at

the still water, mirroring past and present, subject and object.

The gulf spreads wide, the living overlaps the other,

and the reflections are not the same.

“I’m a strange new kind of in-between thing, aren’t I?”

“Not at home with the dead nor with the living.”

Spotted clear drops collect themselves,

hanging from woven spider webs under the chair,

in heavy air, still and same and still until

morning sticks and the drops fall

in outstretched palms, sound

pit pat pit pat.

The greatest regret:

I no longer fit

in the space between your waist and thigh.

If I fit in your arms,

if I could breathe in time with you,

if my voice didn't die in my throat,

If I could bring myself to live:

with the ease that sets when you

used to scratch my scalp,

without a crease shriveling my brow

without gnaw marks in my cheek,

with love.

if we could bring ourselves

to throw out what-ifs,

acknowledge the space, and

how conditionals can't save us from

the space in between

what we were, what we want,

what we should be,

and what we become,

then forgive me for choosing

to hang from still leaves

and fall.